DAOrayaki DAO Research Bonus Pool:

Funding address: 0xCd7da526f5C943126fa9E6f63b7774fA89E88d71

Voting progress: DAO Committee 3/7 passed

Total bounty: 120USDC

DAOrayaki DAO Research Bonus Pool:

Voting progress: DAO Committee 3/7 passed

Contributors: Demo, DAOctor @DAOrayaki

Total bounty: 120USDC

Types of research: DAOs, Prehistory, Cooperatives, gaming guilds, and the networks to come

Original Author: Keikreutler

Contributors: Demo, DAOctor @DAOrayaki

Original: A Prehistory of DAOs

The year is 1996. John Perry Barlow is about to declare, The Internet is made of transactions, relationships, and ideas themselves

From the perspective of the web today, one could argue that only the first part of Barlows statement is true. The spectacle surrounding digital assets suggests that we have reached a new level of financialization, continuing a trajectory where more of our online behavior becomes direct economic interaction. While blockchain-based digital assets are suitable for speculative financial markets, they are not the only application of the technology. During the peak of this hype cycle, we could see relationships built by new peer-to-peer institutions take root underneath.

Computers of the early world? The Ruzname-i dairevi astronomical table for the Arebi (Islamic) and Rumi (Julian) calendars provides a chronological account of the changing seasons, the entry of the sun into the zodiac, and the times of summer and sunset. Image: Wellcome Series

One of the first core applications of public blockchains is global digital assets. It is global in the sense that they do not rely on institutions to prove that they have not been double-spent: the Mystery Cat on the Moon NFT is the only Mystery Cat on the Moon NFT corresponding to its token. The utility of provable uniqueness also extends to types of relationships beyond direct economic exchange, leading many to think as much about new forms of finance as new forms of organization.

However, the prospect of new forms of organization assisted by information technology is inseparable from the background of the invention of the Internet. In 1995, the year before John Perry Barlow published his Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, another written work that would influence early Internet political ideology appeared: David Rofer Tribes, Institutions, Markets, Networks (TIMN) by David Ronfeldt. The TIMN report was funded by the RAND Corporation.

In Dr. Strangelove, it is insinuated as BLAND Corporation, a nonprofit research and development think tank founded in 1948 to provide information to the US military, government, and industry to this day. Because the Internet started in this militarized environment, and we will start here too.

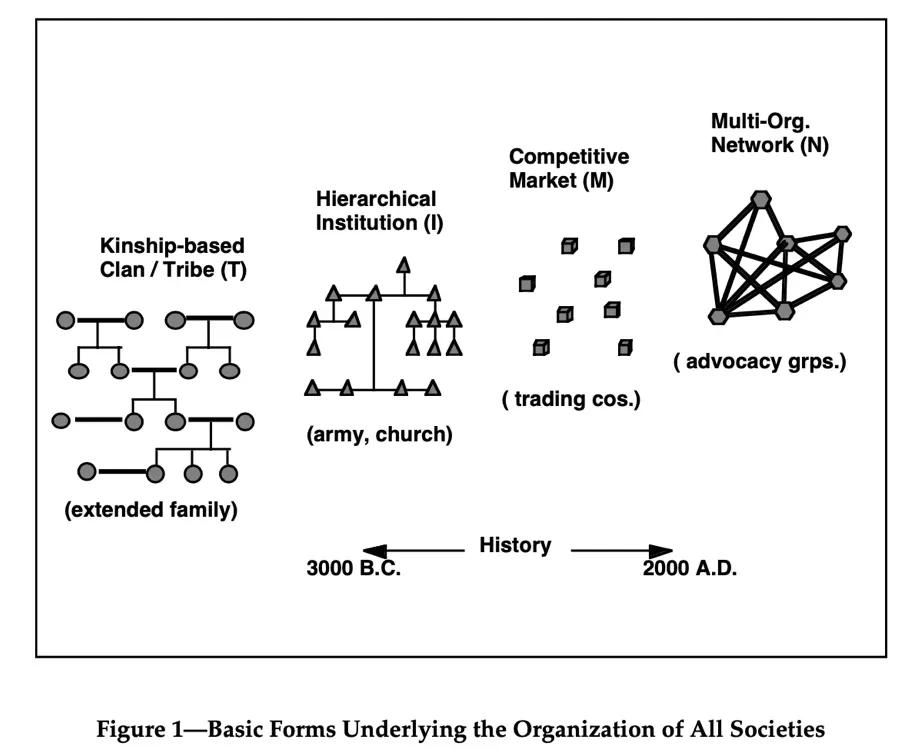

The Times report creates a narrative of social evolution in which humans progress through four distinct forms of organization:

(T) Tribes have the principles of social organization of kinship, clan and lineage.

(1) Institutions have a social organization principle of hierarchy. (M) Markets have the principle of social organization of competitive exchange. (N) The network has a social organizing principle of layered collaborative exchange. Hierarchical here means that the organization is unhierarchical, unranked, or has the capability to be ranked in multiple ways.

While new organizational forms evolved over time, previous organizational forms grew within their scope of activity, even if that scope was newly limited, citing how markets raised taxes to support the institutional state, despite constraints in other respects to participate in direct economic exchange.

The reports institutional biases are evident, such as its equating of progress with Western liberal democracy, and its account of social evolution may seem reductive at best. However, its arguments provide historical context for the political ideologies that decentralized organizations draw from, consciously or not. Nowhere is this more evident than in the reports identification of the newest form of organization: the network.

While networks have historically existed, new information technologies, emphasizing partnerships with outsized impact on institutions across jurisdictions and markets, facilitated the growth of keiretsus and other distributed, network-like global There are more and more so-called virtual companies, Ronfeldt points out. However, the main domain of multi-organizational networks has been neither the public nor the private sector, at least traditionally.

Instead, they are most likely to alter the third autonomous social sector, identified in the report as civil society. In the 1995 organizational landscape, which included non-governmental organizations (NGOs), grassroots organizations and private voluntary organizations, civil society would be strengthened through multi-organizational networks and potentially address issues surrounding inequality, bureaucracy and failures of previous organizational forms. sexual issues.

The report presents a sweet political image of the network: While the development of institutional and market organizational forms leads to an emphasis on competitive advantage, the development of multi-organizational network forms may shift the emphasis to cooperative advantage. Behind this political display is the imperial soft power that NGOs will export globally over the next decade. All of these languages may feel familiar to those currently working on web3, despite this dubious ideological inheritance that is often overlooked.

Since the report concludes by highlighting the three-letter acronym for Civil Society Organization, NGO, NPO, and PCO, naturally one of the future is missing: DAO.

secondary title

Chimeric terms:

DAO stands for Decentralized Autonomous Organization.

DAOs arose from imagining how decentralized technology features such as global digital assets, censorship resistance, and automated operations would change the way organizations operate. Originally known as a Decentralized Autonomous Company (DAC), the more general term DAO emerged in the Ethereum blockchain community. Based on Vitalik Buterins DAO, DAC, DA, and More: An Incomplete Terminology Guide 2014, a DAO can be described as a capitalized organization in which software protocols inform its operations, placing automation at its center and humans at the periphery. For example, a software agreement can specify the conditions under which an organization automatically distributes funds to its members. This has led to the lingering idea that organizational value can be automated and enforced by code, which may falsely imply that tacit knowledge can be fully expressed in software protocols. Despite the terms hypothetical ideas, when DAOs went from theory to experiment, the community largely redefined the term DAO to mean an unstoppable or censorship-resistant enterprise. The first DAO, called The DAO, became one of the biggest spectacle to date in the Ethereum blockchain community in 2016, raising over $150 million in ETH in 2016 as a decentralized venture fund. However, the experiment proved short-lived when The DAO was hacked a month after launch.

It wasnt until a few years later that large-scale initiatives related to DAOs received attention again. From then to now, DAO has diverged from its original purpose, continuing to serve as a chimeric term that and its implementations vary according to their cultural context. Every speculation in the market, however noisy it is, creates new signals that DAOs can deploy, bringing descriptive, technical, and cultural improvements to the concept in practice. While it has been joked that a group splitting the lunch bill might be a DAO, to avoid overgeneralizing (9), DAOs will be limited here to focus on examples in the Ethereum blockchain community, although other communities are similar Coordination is also important. By 2021, DAOs could be described as voluntary associations aligned with the operating principles of digital cooperativeism. As voluntary associations, they are cross-jurisdictional ways for strangers, friends or unlikely allies to come together anonymously to achieve a common goal, supported by token models, incentives and governance. Members of a DAO can have representative ownership of their digital assets through tokens, which often also serve as governance rights.

The decentralized technology ecosystem tends to describe a phenomenon by its technical products. However, as Ruth Catlow, co-founder of Furtherfield and the DECAL Decentralized Art Lab, points out, “We need to build culture before we build structure” (10). While the following overview of DAO tools provides a concrete description of the concepts in practice, it is critical to remember that DAOs are ultimately coordinated through a collective atmosphere.

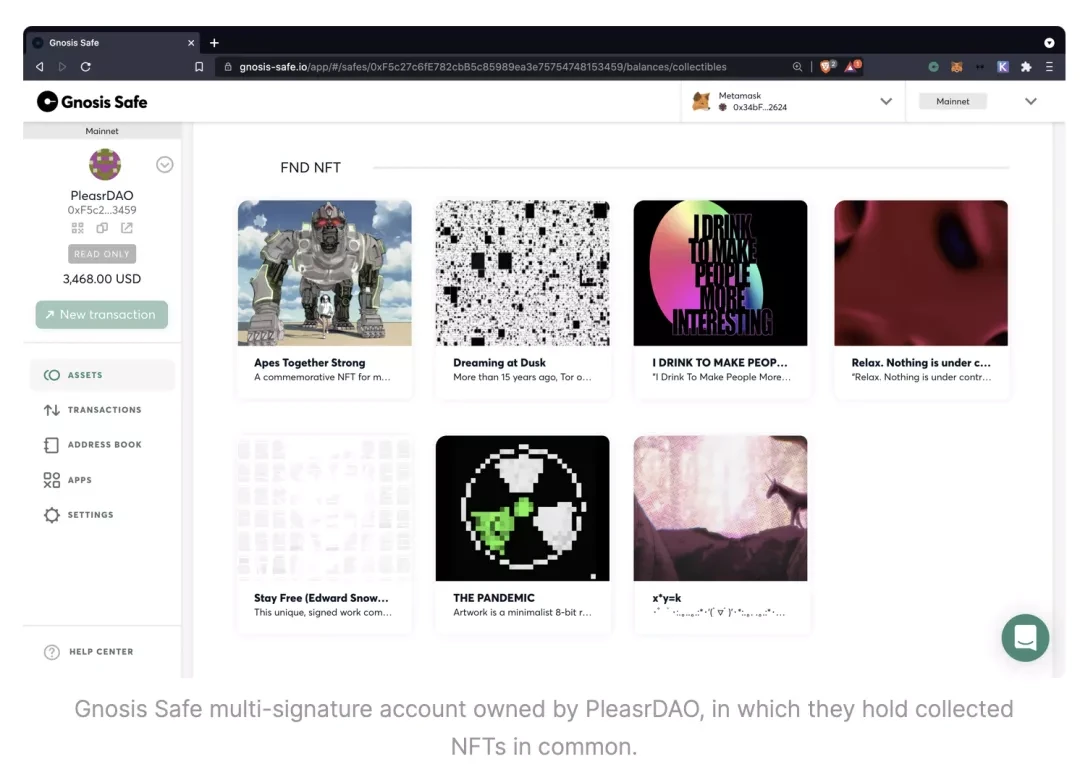

In their simplest form, DAO tools are described as group chats and bank accounts (11). In 2021, this usually takes the form of Discord servers and Gnosis Safe Multisig, a web3 platform for creating multi-signature accounts. Multi-signature accounts allow anonymous parties across jurisdictions to pool and manage funds in minutes, far beyond the capabilities of traditional joint bank accounts. This minimum viable DAO, or MVD tool, will shine in the first half of 2021 with initiatives like PleasrDAO.

PleasrDAO is an NFT of collective bidding artist ppleasr. Given the rising price of NFT digital art auctions, the idea behind PleasrDAO is simple: A group of fans using multi-signature accounts can pool funds to bid on an auction and win the auction by competing against other leading bidders through co-holding. After winning their first eponymous auction, PleasrDAO went on to collect other pieces such as Stay Free, an NFT backed by Edward Snowden for an independent media charity, which totaled 22,000 ETH or $5.4 million equivalent at the time. Their repeated successful missions mean that, while still acting as collectors, PleasrDAO will expand their scope to start incubating projects by their community. Initiatives like PleasrDAO have the best hope of challenging institutional collectors by expanding membership, inviting the artists they collect like ppleasr to in turn become members of the collective.

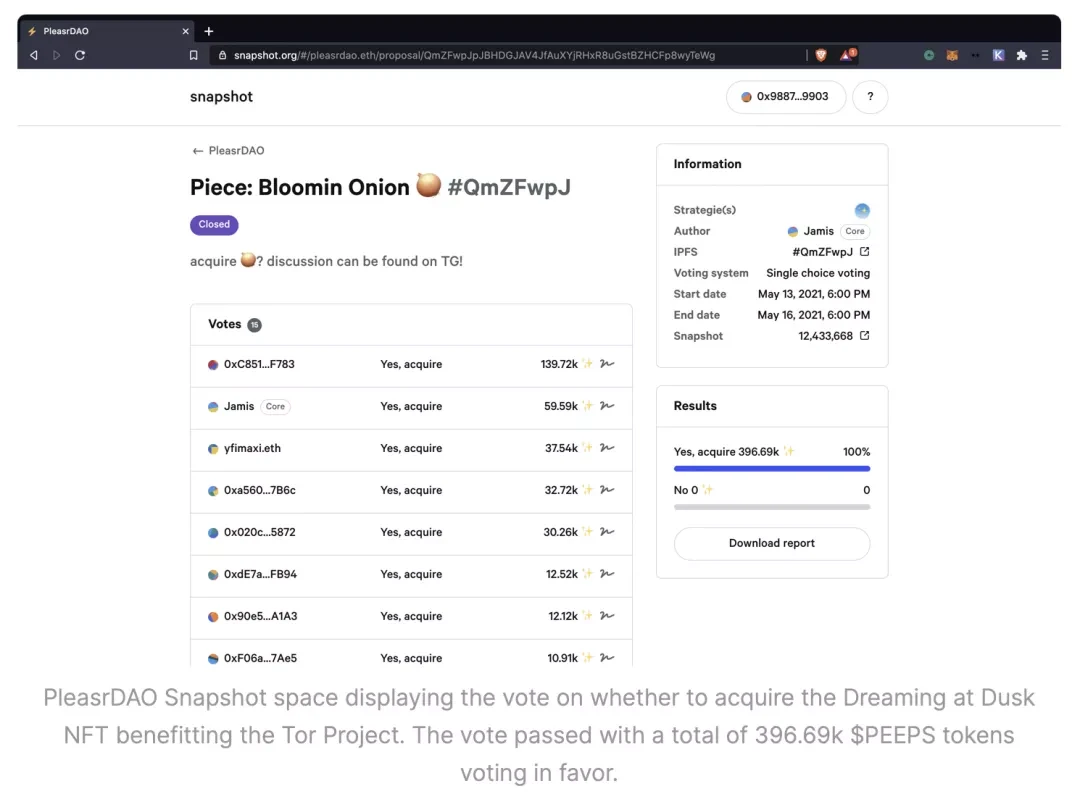

While group chats and multi-signature accounts may be enough to initiate DAO missions, tokens often become the next step in embracing the principles of digital cooperation. For example, PleasrDAO issued $PEEPS, an internally distributed token to represent members’ interests in collections, which they are considering making public to subdivide ownership of their collections. Similar experiments, such as PartyDAO, use tokens, the $PARTY token represents co-ownership of group chat membership, governance rights, and production value managed by the DAO. It is important to note that PleasrDAO and PartyDAO are not flat hierarchies, as they both elect a group of individuals to manage their multi-signature account vaults. Although initially focused on shorter missions, PleasrDAO and PartyDAO are both evolving toward a longer-term vision as collectors, investors, and incubators, using tokens to represent joint ownership in the spirit of digital collaboration. Tokenization creates both opportunities and challenges for the upcoming web.

secondary title

A New Dimension for Cooperative Movement:

Going back to their origins, todays DAOs are DAO-like in that they emphasize open participation and economic value creation, while their culture veers more toward specific niches and social connections. In the example above, one term is intentionally vague: governance. Today, many DAOs use lightweight Snapshot platforms for governance (13). On Snapshot, each DAO has a space to create and vote on proposals. For example, both PleasrDAO and PartyDAO have a Snapshot space where they hold public votes on collective decisions. Snapshot weights vote based on the amount of DAO-specific tokens held by addresses, such as the $PEEPS token in PleasrDAO.

The topic of governance has its own history within the crypto ecosystem and will not be elaborated here. Notably, the MolochDAO initiative, which uses the classic font Papyrus and makes heavy references to gaming guilds, reignited the flames of decentralized governance in the wake of The DAO hack. MolochDAO went on to inspire a plethora of new DAOs, many of which were directly forked.

The history of DAOs in this article is far from complete, as other projects such as Aragon, Colony, DAOhaus, and DAOstack continue to develop platforms for DAOs, and modular initiatives such as Block Science and the Commons Stack emerge.

These projects provide DAO tools that support many governance mechanisms. However, no prehistory of DAOs would be complete without the frequently mentioned relationship to platform corporatism.

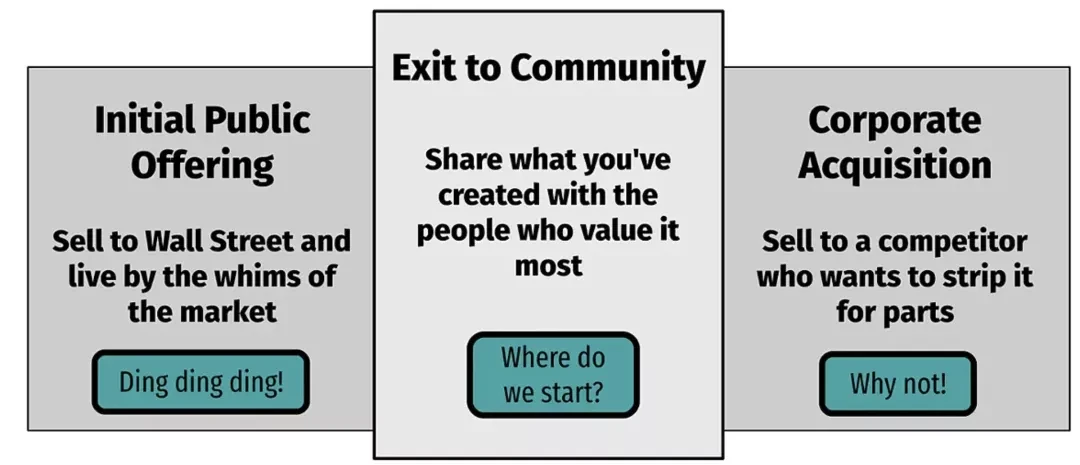

Building on decades of public advocacy, the term platform co-operativeism coined by Trebor Scholz and the concept of exit communities outlined by Nathan Schneider have intersected with the crypto space through articles such as Jesse Waldens The Economics of Ownership.

These taglines advocate for a platform that is owned, developed, and managed by a community of users. Specifically, the concept of “exiting the community” affects decentralized governance by articulating a third way in which a company develops ownership.

Exit communities grow in practice through initiatives such as DXdao, which aims to give community ownership, governance, and value to software protocols.

Today, with many decentralized finance software protocols directing their development through DAOs, it is clear that software protocols can either exit the community or build with it. Because DAOs use early software tools, it makes sense that their first users and use cases would involve the governance of digital assets, such as software protocols. The digital primacy of DAOs may be one reason why their similarities to earlier cooperative movements are often overlooked.

Today, the International Cooperative Federation defines a cooperative as “a self-governing association of persons voluntarily united to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprises” (14). A cooperative can also be defined by its legal entity structure, which indicates that a cooperative is a corporation that is not owned by shareholders, but by its members. A pivotal moment in the history of the Co-operative was the establishment of the Rochdale Principles, established in 1844 by a weavers guild. The International Cooperative Alliance adopted these operating principles, which still guide cooperatives worldwide:

1. Voluntary and open membership

2. Democratic member control

3. Economic participation of members

4. Autonomy and independence

5. Education, training and information

6. Cooperation among cooperatives

7. Follow the community

While these operating principles have evolved over the past two centuries, todays DAOs can easily enact them. The principles of voluntary and open membership, member economic participation, and community focus translate into the above example of a DAO. The principles of autonomy and independence and cooperation between cooperatives are key to the DAOs thriving as multi-organizational networks, strengthening autonomous social sectors through cross-DAO cooperation.

DAOs could have more thoughtful norms around democratic member control, which cooperatives typically define as one member, one vote. Most DAOs use token voting, that is, one token, one vote. DAOs believe that token ownership represents stakeholders, and the token model is often directly economically relevant to the DAO, such as by charging for software agreements it owns.

This allows DAO members with greater financial interests to have proportionally greater influence. Token voting does not directly contradict cooperative principles, as there are cooperatives that weight votes based on quality such as production. In some cases, this may feel appropriate, but as some DAOs move towards maintaining basic infrastructure, this inequality becomes undesirable. This is partly because not all stakeholders have the buying power to represent their interests, and their practical knowledge may be excluded from governance.

Projects such as the Tornado Cash privacy protocol address this distribution problem by retroactively sending tokens to previous users, thereby making users stakeholders of the protocol (16). The Regen Network project, a public blockchain for ecosystem services, takes another approach to this distribution problem. They set aside 30% of the tokens for land stewards, climate scientists, and other stakeholders in regenerative land management to form a community DAO that participates in network governance. Since tokens are easier to distribute than traditional corporate interests, memberships, or shares, this opens up the possibility for a new form of token-holding company that can incorporate greater governance in governance without increasing operational transaction costs. In-depth practical knowledge. Stakeholders with practical or “tacit” knowledge, such as land stewards in the Regen Network, benefit governance by incorporating informal practices into decision-making. Here, DAOs begin to introduce new dimensions beyond the concepts embraced by the operating principles of digital cooperation.

Therefore, as much as the decision-making mechanism, token distribution mechanisms that identify wider stakeholder participation should be innovated and emphasized as much as possible.

The tokenization of online communities can be a long-running topic of debate. Far from being the best answer to the social media dilemma of Web 2.0, tokenization introduces more financialized relationships. As a guiding light, the goal of web3 applications is to introduce value in historically rejected relationships, such as labor and the environment, rather than create new financialized relationships. In this context, tokens become a useful mechanism for a DAO whose mission is to create economic value in three ways:

2. Assign governance rights

3. Align DAO ecosystem

Tokenization introduces a strong cultural norm for early-stage organizations: expect transparent co-ownership of assets from the start. Tensions between more traditional corporate structures that pay dividends and DAOs persist (17). Because most DAOs represent governance rights through tokens, tokens, in a sense, bring the Trojan horse principle of cooperatives directly into highly financialized spaces. These are literally two important aspects of a coin, and as such, tokenization should not be overlooked. Tokens may be the key to unlocking the ownership economy, but in order to achieve a fairer version of the future, we must now participate in building the culture around token distribution, mediation, and governance. This becomes important because, unlike shares in a co-op, many of the governance tokens can be sold on secondary markets. While this makes entry into organizations easier, DAOs could learn from co-ops emphasis on long-termism by building more cultural patterns around token vesting, limited transferability, or more experimental mechanisms.

Just as DAOs can learn from co-op case studies, in two-way exchanges DAOs can introduce more forms of decentralized governance to co-ops. This is the case Morshed Mannan makes in Fostering Worker Cooperatives with Blockchain Technology: Lessons from the Colonial Project, which cites how cooperatives often face “coordination problems as entities expand across The negative trends of “cooperativity” and solidarity as they internationalize. The dilemmas faced by cooperatives, such as funding, governance, and coordination across jurisdictions, are directly addressed by DAOs. Cooperativeism as an agreement rather than a corporate structure, in their In neologisms, DAOs can encourage a cultural space that transcends traditional sectors.

secondary title

Gilded Age:

While DAOs may accidentally embrace the operating principles of previous cooperatives, they also slyly resemble enclaves from other online cultures. In massively multiplayer online games (MMOs), they learn the most from guilds.

As role-playing computer games came online in the 1990s, it meant that large numbers of players could share a game world: an environment with multiple goals, activities, and subplots. Early holistic examples of MMOs include The Realm Online, Ultima Online, and EverQuest, which led to more classic games like World of Warcraft and EVE Online. In many of these examples, players are largely free to set their own goals, guided loosely by open game world narrative, revelation, and risk (18), and because of this narrative freedom, players form groups to accomplish unattainable common goals. Target single player game. Broadly known as guilds, clans, or alliances, these groups range in number from 40 to 1,000 participants, and their goals may include defeating difficult enemies or building useful tools.

In order to achieve these goals, cultural patterns emerge in guilds, and sometimes the tools released by game world developers for guilds do not match their actual needs. In one example of EVE Online, the developers of the game world created an interface for players to create corporations that allow players to distribute shares. In practice, this feature of allocating shares is rarely used because it does not enhance existing cultural patterns. Instead, using EVE Onlines in-game browser and data API, many guilds have developed their own tools to achieve their goals. Similarities between gaming guilds and DAOs can be drawn here, as the current wave of DAOs tends to use a combination of composable tools, such as a Snapshot voting platform connected to a Gnosis Safe multi-signature account, rather than a platform that is overly anticipated Participants case.

While the specific feature of distributing company shares may not have sprung up in EVE Online, game guilds often employ the economics of redistribution. The immense importance of MMO markets, from Varrock to gold farming, to decentralized finance will be the subject of a later article, but one economic practice may be closely related to DAOs: Dragon Killing Points (DKP).

Historically, when dragons were the most frequently encountered enemies in MMOs, DKPs were named after them as a distribution system within and sometimes across guilds.

Complex, ongoing missions performed by guilds, such as slaying a dragon, are often called raids and can range in length from hours to days. At the end of a raid, slain enemies drop an in-game item called loot, and the guild must decide how to distribute it.

Because guilds require diverse and complementary player skill sets over long periods of time, its important to have the same people working together again, and the perceived fairness of often scarce loot distribution is critical to this. As guilds mature, they often evolve different loot distribution systems, starting with random distribution for example, gradually moving to random distribution by participation weight, and often through an informal scoring system (such as DKP). DKP acts as a private currency system separate from any existing currency in the game world, and guild members earn them based on their participation in raids. Guild members can choose to spend these points in exchange for loot after a raid.

The DKP was originally designed by a guild for the EverQuest MMO in 1999, and despite minor tweaks, it has been embraced by many guilds across many game worlds. Ed Castranova and Joshua Fairfield detail an example in Dragon Kill Points: A Summary Whitepaper: the Leftovers DKP system, which maximizes the number of participants by not being tied to a specific guild. As Castellanova and Fairfield write, In fact, this organization is actually the highest distribution agency in the population. If there is an emergency government in the [World of Warcraft server] Silver Hand, it is leftovers Leftovers. The Leftovers DKP system has some limitations: loot can only be picked up after a battle, and cannot be transferred between players in World of Warcraft. The Leftovers DKP system has a small group of informally appointed managers: players laboriously set up and maintain a database of loot prices in DKP through open dialogue. When loot drops, players with DKP can choose to spend them on specific items, and all bids and trades are public. As a zero sum, the Leftovers DKP system then divides the spent DKP points equally among all other guild members participating in the raid.

As Castranova and Fairfield point out, DKP complements the existing currency of the game world, both for efficient distribution and for social cohesion, making it possible to exchange time (spent on raids for which individuals are not compensated) for goods (acquired) .in those raids where individuals won the loot).

In World of Warcraft in particular, since loot cannot be transferred between players, the loot itself also has a strong signaling function, indicating that players have meaningfully participated in raids over time. This DKP system precedes the mechanisms of DAO platforms in development today, such as Aragon, Colony, and DAOstack, which all offer mechanisms for distributing reputation tokens based on member participation, with rewards for successful proposals, bounties, or campaigns: what could be Called raid in other game worlds. These reputation tokens complement other economic systems supported by the DAO platform, such as DAO-specific tokens or other assets in the multi-signature account pool. Often used as an alternative model to Regal Single Token, One Vote Model, Reputation Tokens, earned through participation rather than purchasing power, providing greater voting power in a DAO that accumulates over time. DAOs can learn from DKP, which instead acts as a participation-based private currency system that can be used for other digital assets, not just accumulated over time.

In addition to efficient distribution, contextual reputation, and signaling capabilities, the DKP system has another implication for DAOs: generally all guilds resolve disputes independently of the traditional court system, although these disputes involve expensive equity. This is highly relevant to DAO tools like Aragons Digital Jurisdiction or Kleros Decentralized Arbitration Service that aim to provide internet-native dispute resolution tools. In fact, DAO tools often attempt to technically solve problems that gaming guilds have been culturally refining for decades, and it may be time for DAOs and gaming guilds to more closely fuse their practical knowledge.

Another subtle cultural pattern of gaming guilds has to do with their explicit economic structure. As researcher Joshua Citarella points out, many DKP systems resemble a form of market socialism in which goods are publicly owned but allocated by the market. Citarella also goes on to point out that while the DKP system resembles market socialism and the players who participate in it are generally happy, many of those players would never accept the label of market socialism politically. Shadow economics might be an appropriate term when a group operates through a form of economy that doesnt label itself as: DAOs as cooperative agreements, gaming guilds as market socialism. This trend has left such interesting political areas as gaming guilds underexplored, since gaming guilds are generally not required to wear their own flags. On the one hand, this may be more of a feature than a bug, as the invention of new terms like DAO, rather than reliance on specifications, fuels their enthusiastic embrace in part.

While this may lead to ignoring their prehistoric history, DAOs retain a powerful ambiguity in which their burgeoning political ambitions do not yet have a fully familiar aesthetic expression. This can be chosen for several different purposes. For example, we can imagine a DAO whose treasury self-destructs when global temperatures rise above 2C, like terra0s NFT, complete with a shiny, humble mascot avatar

Such a DAO might attract participation from those not attracted to the familiar green aesthetic of most climate initiatives, and it might expand participation in political goals by creating a new culture around it. Momentum for something new is always good for something, and the question becomes how to foster DAOs that can build covert unity across ideological divides.

The Birth of a Constellation:

While the comprehensive prehistory of DAOs can provide insight into the past, many proponents of DAOs have a core belief in their impact on the future: DAOs can outperform the competition by partnering with modern corporations.

While DAO tools like Gnosis Safe enable this today, the promise of infinitely scalable organizations in general is a long way off. Often, even the promise of a DAO can overshadow its utility in practice. In The Dissensus Protocol: Governing Differences in Online Peer Community, Jaya Klara Brekke, Kate Beecroft, and Francesca Pick focus on a case study of Genesis DAO, a collective centered around the DAOstack platform. They write:

Genesis DAO is a good example of a unique characteristic shared by many DAOs, namely that they consist of highly motivated groups formed around a set of ideas about governance, rather than governance as a means to achieve some common mission means. In other words, its tool-centric and focused on one main action: allocating funds to proposals. It is unusual for strangers to immediately start making financial decisions together without time to build coherence and trust.

This is actually the promise of projects like Genesis DAO: the technology will bypass the need to develop trustful relationships, meaning thousands of people will be able to rally around goals, take action, and even spend money together as a group

Like the early example above of EVE Online players not using an interface to allocate stakes in companies issued by game developers, tool-centric development and the assumption that tools automatically create useful cultural patterns must be reconsidered. Unlike governance technology protocols that reduce the need for trust relationships, DAOs can be implemented by iteratively developing highly composable tools to coordinate between different levels of consistency and trust. Ultimately, the efficiency DAOs seek may not be defined as an economic function, but as a matter of better governance: supported by deeper practical knowledge in infinite games.

secondary title

Layers of DAOs:

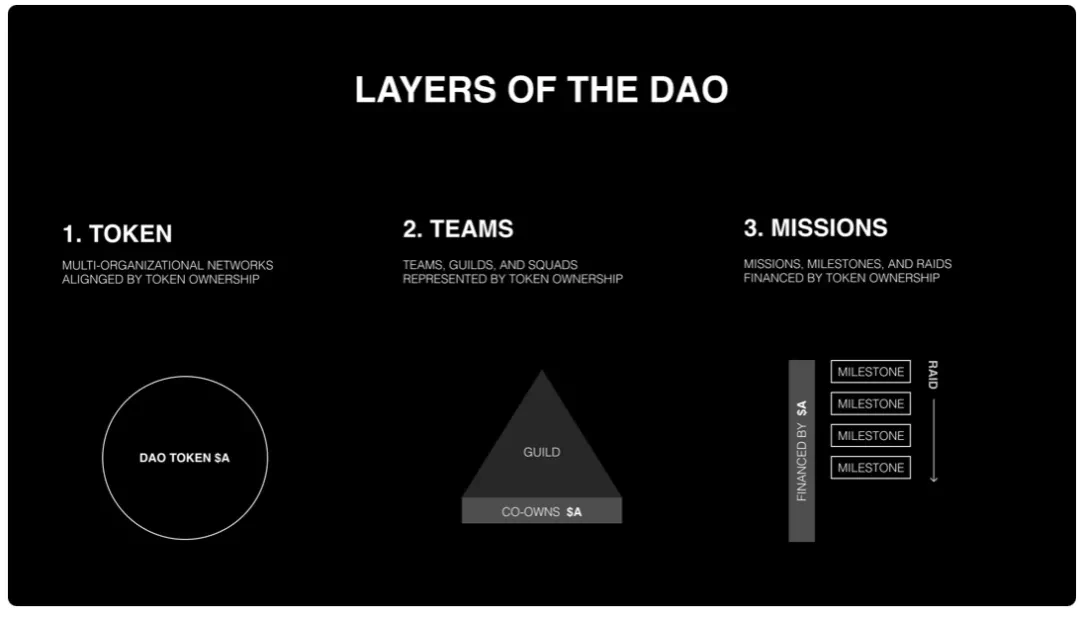

The DAO will not be the unified, non-hierarchical network some people imagine. Instead, DAOs coordinate between different levels of consistency and trust. On Ownership in Cryptonetworks, Patrick Rawson argues that for DAOs, distributing ownership to squad-like entities with more specialized goals is a key long-term issue that needs to be addressed in order to enable meaningful work. These squad-like entities are smaller teams with trust relationships, perhaps not unlike the gaming guilds in the example above, that perform missions of consistent value with the DAO. On closer inspection, effective DAOs start to behave more like team networks, such as the MONDRAGON Corporation network of 100 affiliated cooperatives, than the loosely coordinated swarm intelligence they may emerge from afar. Inspired by Rosens analysis, we can roughly outline the three layers of a DAO:

1. Tokens: A multi-organizational network aligned by token ownership

2. Teams: teams, guilds, squads represented by token ownership

3. Missions: Missions, milestones and raids funded by token ownership

From these layers, a hierarchical network emerges, which means an organization with the ability to rank in multiple ways.

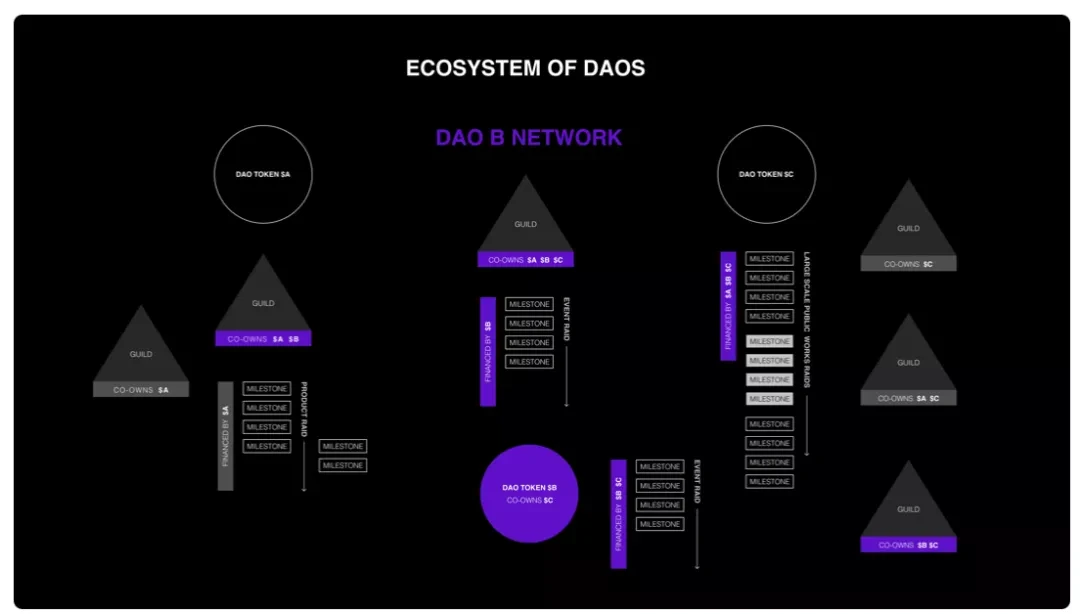

An example of a DAO where tokens, teams, and tasks are distributed across multiple DAO networks that can be ranked or categorized in a variety of ways.

In an ecosystem where distribution of ownership is a priority, the token encourages the DAO network to be governed by its members. Tokens, teams, and missions are not limited to the quasi-institutional boundaries of a single DAO, but can and, in order to meaningfully decentralize control of the network, should be represented by token ownership across multiple DAOs. An ecosystem emerges that differs from the control network of multinational corporations, but importantly, the ecosystem does not have a single center of command and reduces transaction costs across different levels of trust. As Rosen writes, “As long as the collective memory circulates freely within a given [DAO network], discovered problem solutions can be reused.” When we think of DAOs as multi-organizational networks aligned through token ownership, The purpose of DAO tools is not only to support the operation of a team, but also to facilitate the collaboration of multiple teams. Funded by PrimeDAO, a DAO-to-DAO (D2D) collaboration mechanism appears to be the most forward-thinking effort in these lines, and could eventually surpass traditional business-to-business (B2B) offerings. The Gnosis Guild team, a new squad-like entity emerging from stealth mode, also emphasizes DAO-to-DAO tools and uses a new set of DAO tools called Zodiac.

Revisiting the promise of DAOs, their potential to incorporate deeper practical knowledge in governance does not mean that decisions must involve more and more members with each Teams can easily share with the ecosystem. When we think of DAOs as constellations of teams rather than monoliths, DAOs become networks that allow the free flow of collective memory.

Upcoming web:

TIME RAND reports that this article ends on an odd note. It writes:

Much of the literature on redesigning organizations for the information age focuses on production—increasing productivity, or building new products like the Boeing 777 jetliner. Yet isn’t this a lingering industrial-age mentality? Production organizations are still an important part of organizational ecology. However, we should also consider sensory tissue. Sensory functions are quite different from productive functions and require different organizational models—for example, more network connections to the world outside the office. Identifying suitable designs for various sensory tissues may become a good meta-theme for innovative RD in the coming years.