Original author: Citrini , Analyst

Original translation: Felix, PANews

Affected by the US tariff increase, the global economy seems to have entered a state of disorder. Is the Trump administrations tariff increase a stroke of genius or a bad move? Analyst Citrini published an article reviewing historical tariff events from a historical perspective and gradually analyzing the future economic situation. The following is the full text.

“This may be a wrong view.”

Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1781:

But I find myself inclined to adopt the more modern view, that it would be best for every nation to leave its trade entirely unimpeded. I would only remark, upon the whole, that commerce is the mutual exchange of the necessaries and conveniences of life, and that the freer and less restrained it is, the more prosperous it will be, and the happier will be all the nations which engage in it. The restrictions which every nation imposes on commerce seem to be imposed on its own account, under the pretence of the public good.

In the two weeks since Liberation Day, I have spent one week in the United States and one week in China. In both countries, I have been talking to entrepreneurs affected by the tariffs.

Whether importers or exporters, businesses in these two very different geographies and engaged in varying degrees of international trade have one thing in common: uncertainty.

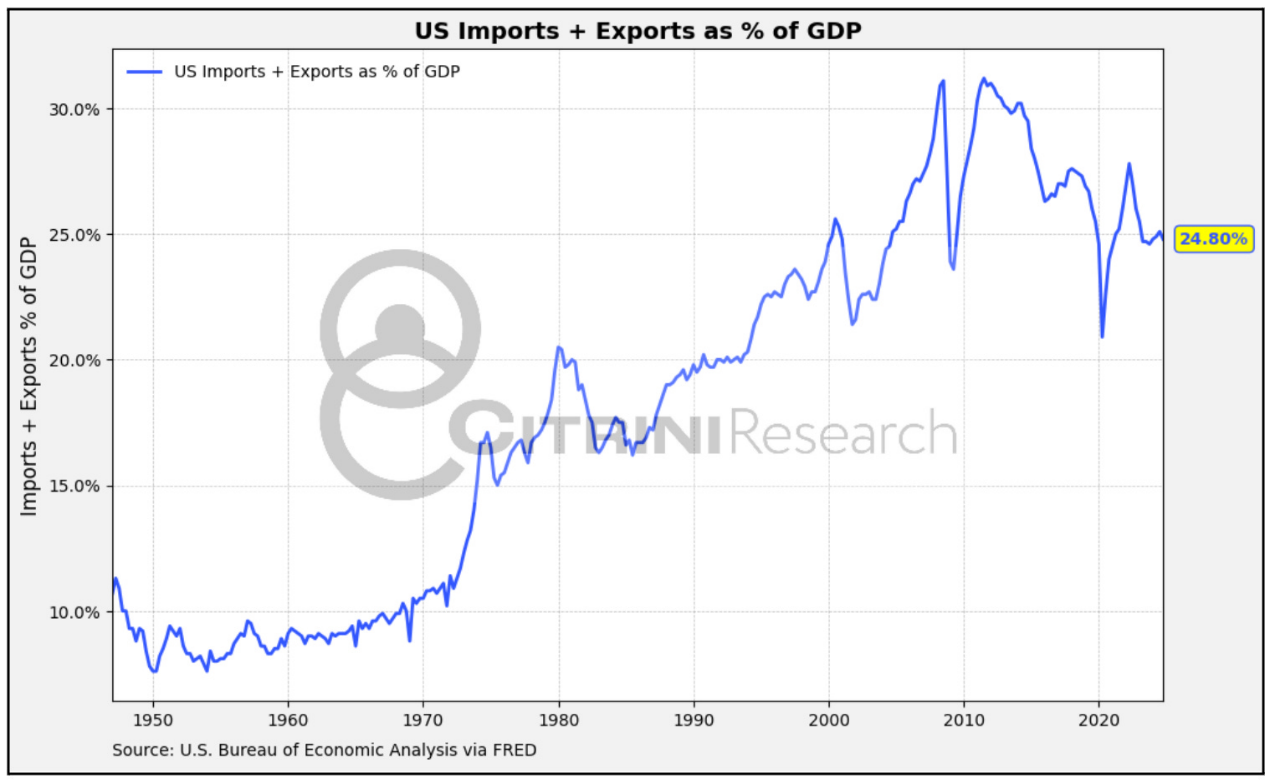

Why the uncertainty? The simple fact is that almost everyone today has only ever experienced a world with increasing globalization, relatively free trade, and the United States as the worlds hegemon and reserve currency.

As this is called into question, investors and operators are clearly looking for a framework that can cope with the future. For a system built on a just-in-time basis, “wait and see” is a deadly strategy, but there is no alternative.

For example, speaking to a top 100 company in Shanghai (ranked by trade volume), it said: We should be rushing to process orders for the festival now. But we have not received any orders so far. Anyone who is not familiar with how importing goods works should be aware that first, it is usually 8 months in advance to order goods for an event. Second, we are going through a pretty big transition.

Chinese companies have historically generally believed that tariffs are something they can adapt to. In the past, a 10% tariff might have caused buyers to seek price cuts from Chinese factories (which they could easily do). While factories obviously can’t cut prices to cope with tariffs over 100%, they do believe they can cut prices to maintain a cost advantage over domestic U.S. manufacturing after the tariffs are imposed. But that doesn’t matter when no one is trading.

I haven’t published a history article in over two years. They weren’t necessarily actionable. But this one seemed to come at the right time. Sometimes the only way to understand the future is to understand the past.

Mercantilism, isolationism, protectionism and many other isms are thrown around randomly, but few people care about the meaning behind them. Although I am not an economist, I am an economic history enthusiast. You might as well treat this article as a popular science article. This article does not talk about what stocks to buy or sell, nor does it make directional judgments on foreign exchange, stocks or interest rates.

Understanding tariffs from a historical perspective

Few people today have actually experienced firsthand the economic conditions during a period of tariffs similar to today’s. The best book on the history of U.S. tariffs is Clashing over Commerce, which I have been reading over and over again over the past few weeks.

The book was written by Douglas Irwin, a famous historian and archaeologist who studies US trade policy, and proposed the 3 R framework for understanding the political economy of tariffs.

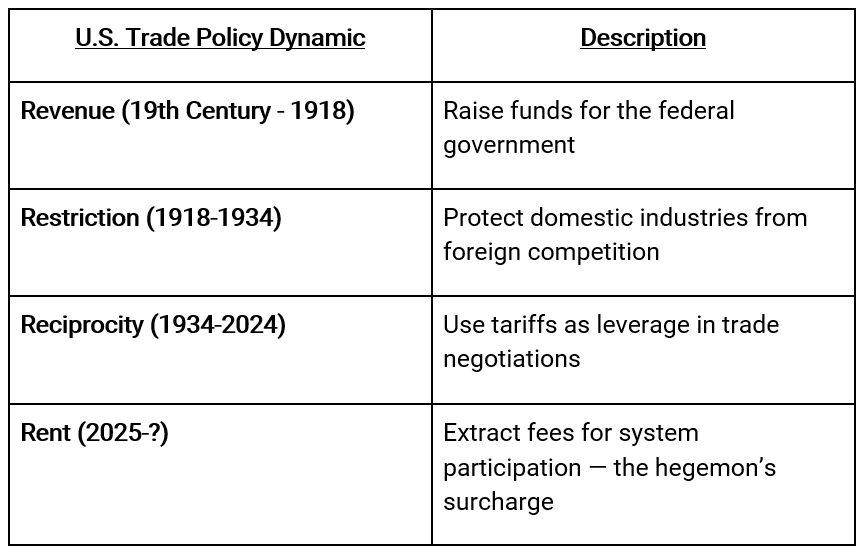

Historically, the “3 R” framework for U.S. tariffs:

income

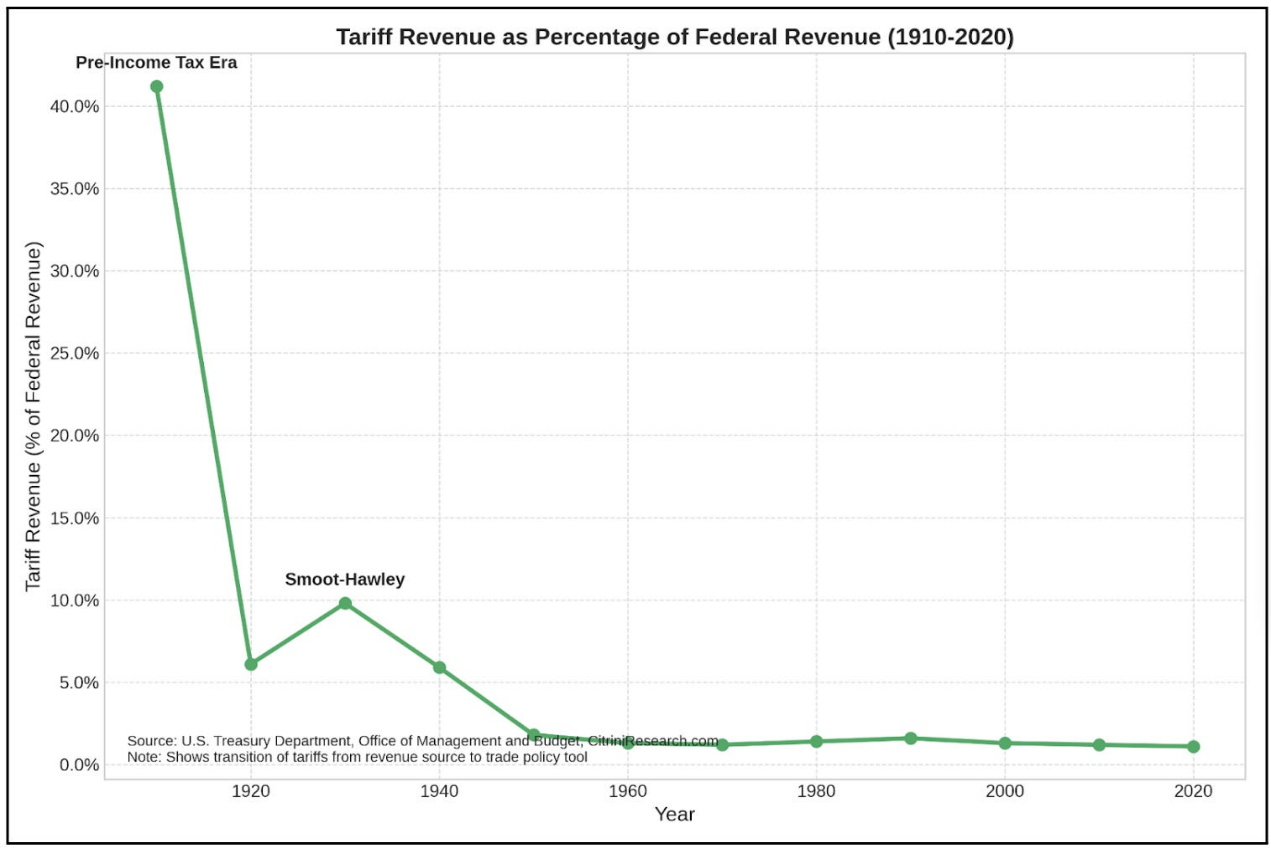

Tariffs were a major source of government revenue, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tariff acts have long been criticized as opaque and difficult to use policy tools, even though they are a major source of government funding, as this 1883 political cartoon illustrates.

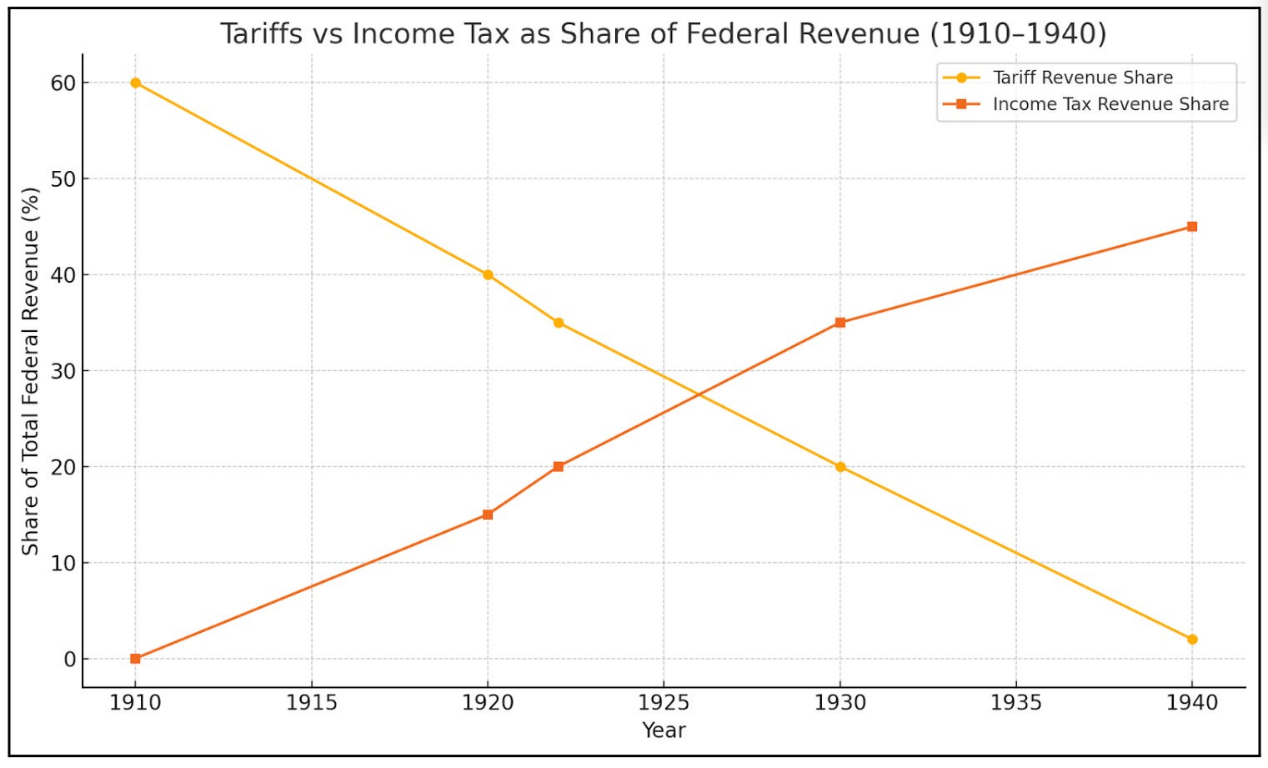

Before the creation of the Internal Revenue Service (1913), the United States had no income tax. In the 19th century, tariffs accounted for more than 90% of government revenue. At the time, tariffs were primarily used to raise revenue, not protectionism - it was seen as a more acceptable way to tax the population that would not cause rebellion. During the first third of the 20th century, less than 15% of American citizens paid income tax. The rest was paid invisibly in the price of imported sugar, lumber, and wool. Tariffs were the original invisible taxes: collected at the port, paid at the checkout.

First, they were a way to finance the state without creating internal taxes that might have sparked a political backlash (a lesson learned from events such as the Whiskey Riots). In Irving’s account, revenue concerns dominated trade policy in the early republic, and even arguments for protectionism had to be framed through a revenue-first lens.

limit

Tariffs are protection for domestic industries.

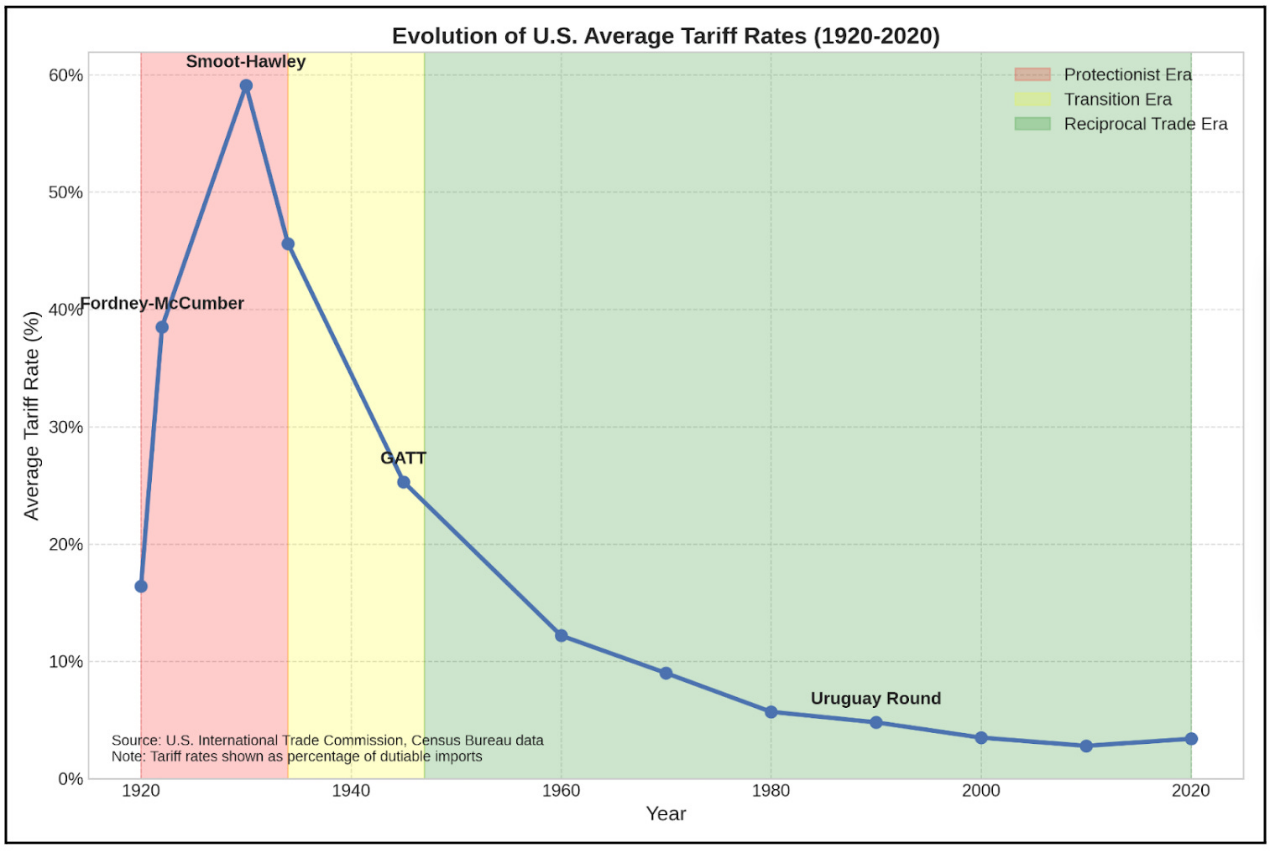

After World War I, tariffs became more of a political tool to cater to foreign competition faced by domestic industries - the driving force of protectionism.

Owen notes that as the revenue motive declined (thanks to the income tax), the incentive to restrict rose. After World War I, tariffs increasingly served the interests of industrial lobbies rather than the Treasury.

Reciprocity

Tariffs are leverage in international trade negotiations.

By 1934, the income tax had gradually replaced tariffs as the primary source of federal funding—a shift accelerated by the New Deal and World War II. Tariffs became a bargaining chip in global trade negotiations.

This was the logic behind the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, the GATT, and later the World Trade Organization. The era of reciprocity marked a move toward liberalization and away from isolationism. The hegemonic power (the United States) traded lower tariffs for access to foreign markets. Tariffs became less of a barrier and more of a lever. VERs, backroom deals designed to force countries to impose export restrictions, replaced tariffs, and were eventually replaced by more and larger free trade agreements. This ushered in the era of multilateral free trade in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

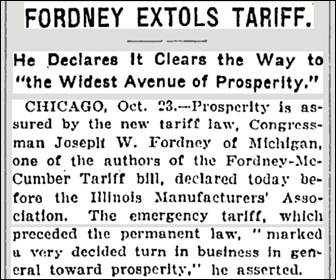

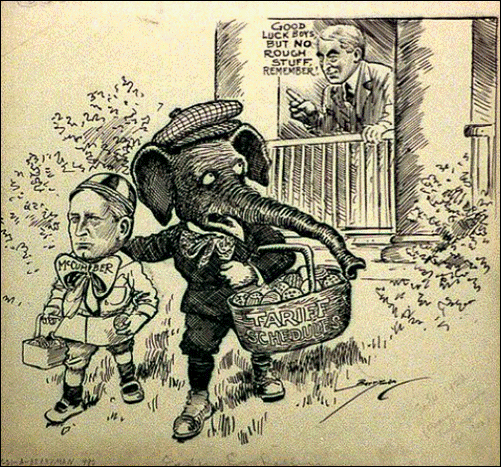

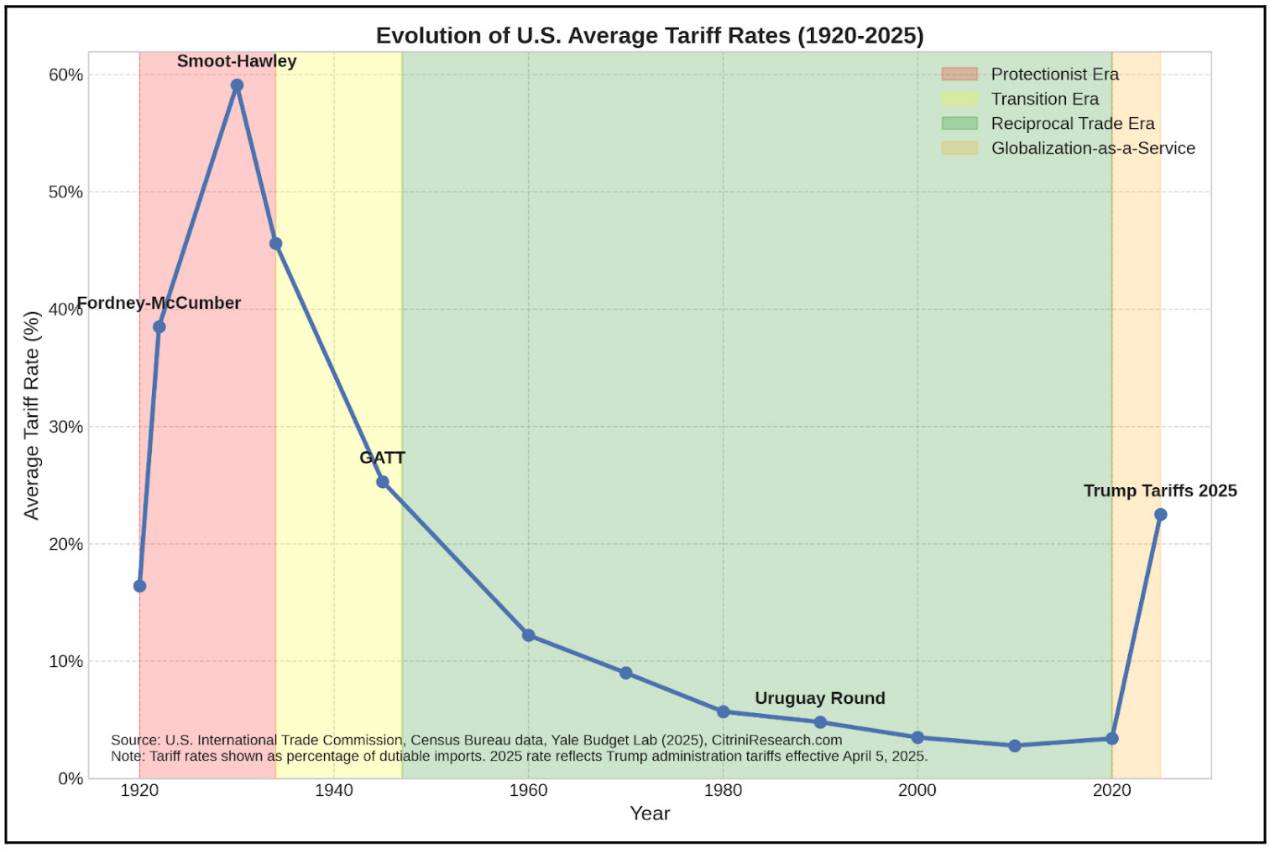

1922: Fordney-Macomber Tariff

The Fordney-Macomber Tariff Act was an early example of protectionist excess and the first real example of a tariff imposed for non-revenue purposes.

Imagine the glorious post-World War I America: American industry was thriving, but farmers were getting poorer. The biggest concern was cheap competition from Europe, but Europe still owed the United States a lot of money, and because the United States kept raising tariffs, Europe couldnt sell anything to the United States. So, obviously, the United States raised tariffs again.

In 1921, Congress passed an emergency tariff bill, followed by the comprehensive Fordney-Macomber Tariff Act of 1922, signed by President Warren Harding.

The law raised tariffs significantly beyond the low level set by the Underwood Tariff Act of 1913 and beyond levels seen since the Civil War (although rates on imports subject to tariffs were roughly the same as under the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909). It also gave the president the power to adjust tariffs by as much as 50% to “equalize production costs at home and abroad.”

The result? Urban industry boomed in the 1920s, agriculture fell into a long recession, and Europes trade surplus, which had helped pay for the wartime supplies from the United States, shrank.

The 1920s were a great decade for American industry. Manufacturing output grew by nearly 50 percent between 1922 and 1929. Unemployment fell from 6.7 percent in 1922 to 3.2 percent in 1923. Industries like steel, chemicals, and automobiles flourished under the protection of tariff barriers. Protected industries expanded, hired more people, and became profitable. Corporate profits nearly doubled during this period.

The opposite was true in agriculture, however. Farm income plummeted from $22 billion in 1919 to $13 billion in 1922. While cities prospered, rural America was mired in a decade-long depression, a decade before the Great Depression. The reason? European markets closed in retaliation, while American farmers, who had expanded production during the war, faced a collapse in demand and prices.

In the 1920s, protectionism brought concentrated benefits. If you were an urban industrial worker, it was a great time. If you were a farmer, it was the beginning of 20 years of misery. The momentum of protectionism had been set, and it was moderately successful for some (though at great cost to others).

1930: Mistake

Massive tariffs, massive depression.

In 1928, Herbert Hoover was riding high. The great engineer won the presidency by a landslide: 444 electoral votes to Al Smith’s 87, Hoover carried more counties than Warren Harding had in 1920, and he won 58 percent of the popular vote. In his inaugural address, the “Prosperity President” promised Americans “a decisive victory over poverty”—words that would soon become his nightmare.

The stock market was soaring, unemployment was low, and Americans were buying cars, radios, and refrigerators at an unprecedented rate. The Fourth Party System, dominated by Republicans since McKinley’s victory in 1896, seemed as entrenched as ever.

Like his Republican predecessors, Hoover was a staunch supporter of protective tariffs. During his campaign, Hoover declared, For 70 years the Republican Party has supported a tariff designed to adequately protect American labor, American industry, and American farms from foreign competition. He made tariff protection, especially for agriculture, a cornerstone of his economic agenda.

As Secretary of Commerce in the Harding and Coolidge administrations, Hoover developed a clear protectionist philosophy: the United States should limit imports to products that the United States could not produce domestically. This was not a radical move, but the culmination of the McKinley Republican tradition and a natural extension of the economic orthodoxy of the Fourth Party system.

Hoover pointed to the “success” of the Fordney-Macomber Tariff Act (total U.S. imports had increased since its passage) as evidence that the United States could simultaneously protect its own industry and expand sales in Canada. “In view of the broad prospects of our trade, we can overlook the fear that an increase in the tariff will so greatly reduce the total volume of our imports as to destroy the ability of other countries to buy from us,” he wrote in 1926. “There is no foundation for the assertion that we cannot have both protective tariffs and increasing foreign trade. Today we have both,” he said in a 1928 campaign speech.

Then came Black Thursday, October 24, 1929, and five days later, Black Tuesday, when the stock market lost more than $30 billion in value, nearly twice the amount the United States had invested in World War I. The roaring 20s came to an abrupt end. Amid the turmoil, tariff negotiations did not subside, but intensified:

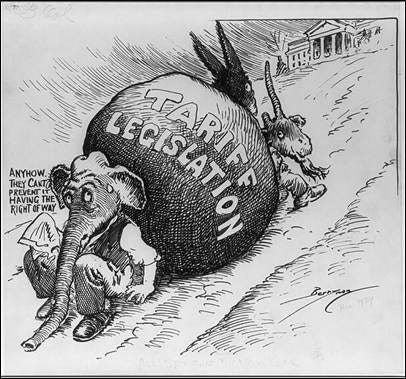

Rather than reconsider tariff legislation in light of the economic shock, Congress doubled down on it. The original agricultural tariff bill evolved into what is now known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, named after its main sponsors, Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon. Originally intended to provide relief to farmers first, the bill ultimately became an industrial protectionist monstrosity.

What began as a targeted effort to protect American farmers turned into a protectionist free-for-all. As the bill moved through Congress in 1929 and early 1930, the number of industries protected grew exponentially. Ultimately, the bill raised tariffs on more than 20,000 imported goods, the highest tariff rates in U.S. history since the “Infamous Tariff” of 1828.

The cartoon depicts an exhausted Republican elephant sitting in the middle of a road, leaning against a large rock labeled TARIFF BILL

The markets weren’t buying it. The 1,028 economists, while they ultimately disagreed on how to get out of the economic mess of the Great Depression, all agreed on one point—if the bill passed, it would be a disaster.

They wrote to Hoover, imploring him to veto the bill:

Front page news, May 8, 1930

Thomas Lamont, a partner at JPMorgan Chase, later recalled: “I nearly fell to my knees and begged Herbert Hoover to veto the stupid Hawley-Smoot Tariff. It would have heightened nationalism around the world.”

Henry Ford spent the night in the White House trying to convince Hoover that the tariff would cause severe economic damage.

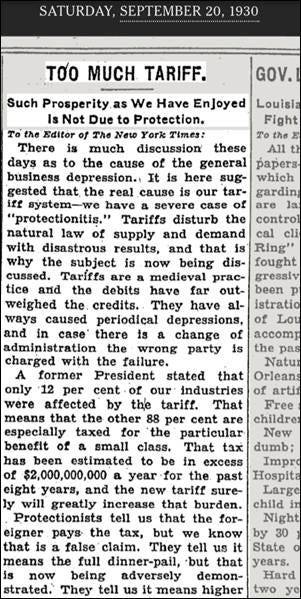

Yet, on June 17, 1930, Hoover signed the bill, a move that was not an instant political suicide, but sufficient. The tariff bill’s unpopularity grew rapidly, as evidenced by the frequent letters to readers in The New York Times:

What happened next was exactly what they say: more than 25 countries retaliated. Global trade collapsed.

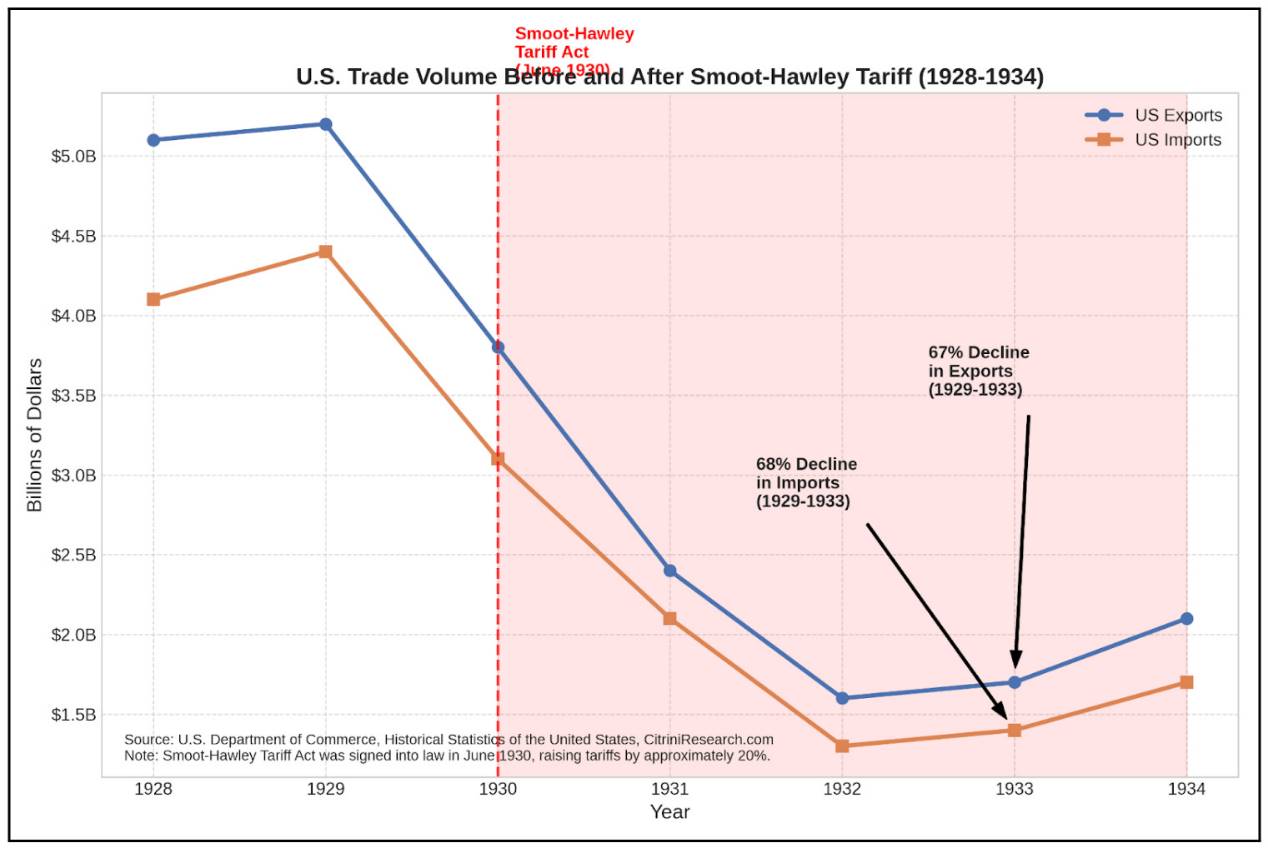

US imports fell from $4.4 billion in 1929 to $1.3 billion in 1932. Exports fell from $5.4 billion to $1.6 billion over the same period. Between 1929 and 1934, world trade fell by about two-thirds.

The stock market crash of 1929 triggered a recession, and the tariffs turned that recession into the Great Depression.

What started as a financial shock turned into a systemic crisis because policies—particularly the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act—stifled supply at a time when demand was falling.

As economists predicted, American consumers and businesses paid the price. The tariffs may have protected some jobs in specific industries, but they destroyed many more by making imported raw materials more expensive and closing foreign markets to American exports.

Recognizing the disaster, Democrats made tariff reform a key campaign platform in the 1930 midterm elections—the first time they had controlled both houses of Congress since 1918. Roosevelt said of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff that it “has forced the nations of the world to erect such high barriers that the trade of the world is being reduced almost to extinction.”

The outcome was obvious: the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was a complete failure.

How did the tariffs differ between 1922 and 1930?

First, let’s look at the starting point: The Fordney-Macomber Tariff Act was implemented during a period of relative global economic growth, especially in the United States. The Roaring 20s masked its many inefficiencies. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, when global demand was already shrinking. It made a bad situation even worse. From a protectionist perspective, tariffs are catalysts for recessions, but they still need a tipping point.

In 1922, businesses and consumers were confident, credit was plentiful, and the financial environment was loose. By 1930, bank failures, stock price declines, and credit crunches were common. At this time, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was introduced, which significantly increased tariffs on 20,000 types of goods. This was undoubtedly a double whammy, indicating that the government had adopted crazy policies at a critical moment, causing investors to panic and worry about further escalation of protectionism.

Second, retaliatory measures. The Fordney-Macomber Tariff Act triggered some limited retaliation (such as measures taken by France in 1928 and selective tariffs by some European countries), but global trade continued to expand in the 1920s. It is easy to measure the damage caused by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in terms of its direct economic impact—raising the average US tariff on subject imports to 59.1%, the highest level since 1830. But the real disaster was not the tariff itself but the global retaliation it triggered.

Canada, then the United States’ largest trading partner, had not previously taken significant retaliatory action against U.S. tariff increases. The Fordney-Macomber Tariff Act of 1922 raised tariffs on important Canadian exports such as wheat, cattle and milk, but Canadian producers viewed these as a return to pre-World War I levels and tolerable.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff was different. Canada’s exports had already been hit hard by a deepening global recession. In July 1930, just after the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was passed, the Liberal government of Canada lost the general election to Conservative leader Richard Bennett. Bennett fulfilled his campaign promise to “force” open world markets by raising tariffs. When you push other countries into a corner, their reactions become increasingly unpredictable.

In September 1930, Canada significantly increased tariffs on 16 American products, which accounted for about 30% of American exports to Canada. Not content with this, Canada also negotiated preferential trade agreements with other Commonwealth countries, further weakening the competitiveness of American exports.

The retaliation did not stop with Canada. By 1932, at least 25 countries had taken retaliatory measures against American goods. Spain instituted the “Weiss Tariff” specifically targeting American cars and tires. Switzerland boycotted American products. France and Italy imposed quota restrictions on American goods. Britain abandoned its traditional free trade policy and adopted protectionist measures. This led to a deteriorating situation, and global trade came to a standstill due to uncertainty and continued escalation of tit-for-tat trade policies.

Third, global financial conditions. In 1922, the United States was still a rising creditor nation, but the gold standard had not yet been fully restored, and many countries were still recovering from World War I. There was no tightly integrated global financial system. However, by 1930, the gold standard had been reestablished worldwide. International trade and debt flows were more closely linked.

Finally, from a symbolic perspective, the Fordney-Macomber Tariff was bad policy, but it was also expected. Tariffs had been the norm for the United States since the Civil War, and many trading partners viewed the Fordney-Macomber Tariff as simply a return to pre-World War I levels. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff, however, was seen as an escalation at a moment of clear global vulnerability. It signaled that the United States was turning inwards at a time when it had already consolidated its creditor status. It undermined confidence in global coordination and may have prompted many countries to abandon the gold standard before long.

Markets and policymakers interpreted Smoot not just as a tariff issue but as a worldview: isolationist, chaotic and irrational. Uncertainty dampened business investment.

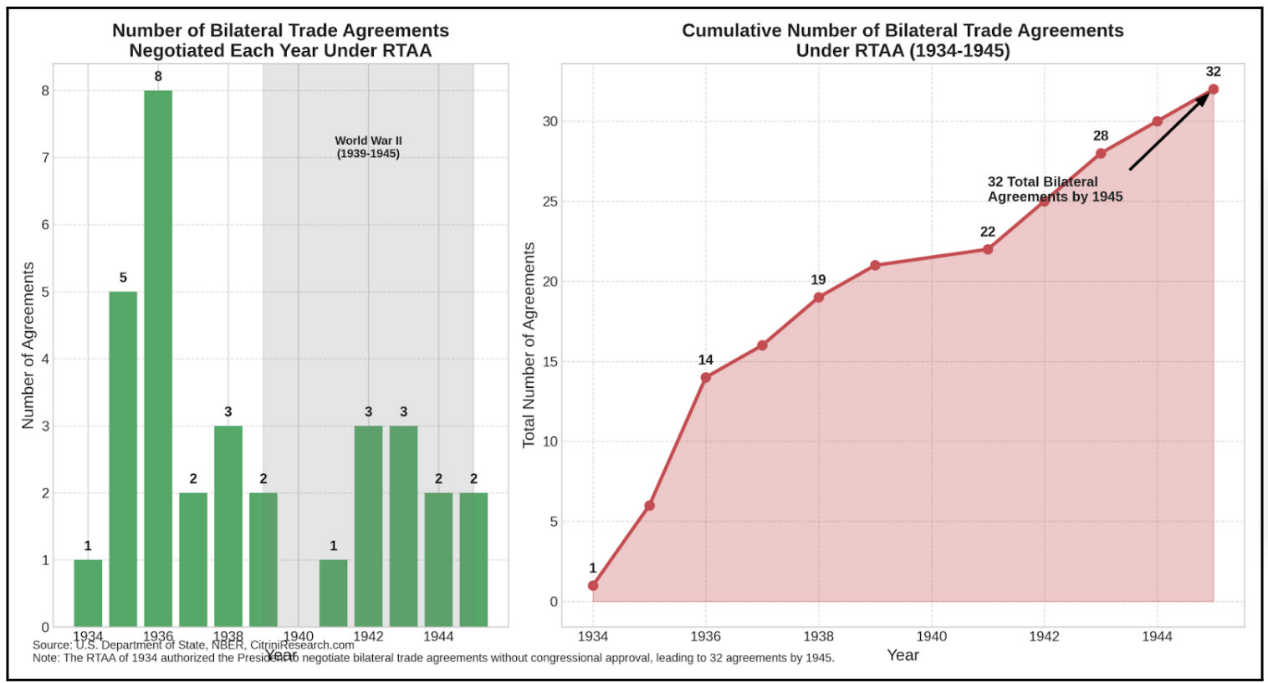

This was a unique and unprecedented disaster in an era of protectionist trade policy, and it paved the way for the election of Roosevelt, who quickly repealed the tariffs and passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA).

1934: RTAA – the beginning of reciprocity

After the protectionist disaster of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, U.S. trade policy reached a crossroads. The passage of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 marked the shift of power over trade policy from Congress to the executive branch, initiating the shift from “restrictive” to “reciprocal.” This institutional change fundamentally altered the way trade policy was made and laid the foundation for the freer trade regime after World War II.

The history of modern international trade begins with Cordell Hull, a Democrat from Tennessee who became the nation’s longest-serving secretary of state. Hull’s background in the agricultural South profoundly influenced his views on tariffs and trade. Unlike his Northern colleagues who sought to protect manufacturing, Hull understood that high tariffs would hurt agricultural exports.

Signing of the United States-Canada Trade Agreement. (Front row, left to right): Cordell Hull, WL Mackenzie King, Franklin Roosevelt, Washington, DC, USA

November 16, 1935

Hull’s appreciation for the international dimensions of trade came gradually. Before his time in Washington, he later recalled, he had “been in the thick of tariff wars—but they were fought at home, over whether high or low tariffs were good or bad for the country. Few people thought about their effects on other countries.”

Rising from the ashes of the failed Smoot-Hawley Tariff, a protectionist law that had severely hampered world trade by spurring retaliatory tariffs, the RTA opened a new path for international cooperation. It introduced three revolutionary concepts that would define the era of reciprocal trade:

Executive Power: For nearly 150 years, Congress has jealously guarded its constitutional power to “regulate commerce with foreign nations,” allowing trade policy to be dictated by local interests. The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act shifted much of the negotiating power to the president, allowing him to reduce tariffs by as much as 50 percent without congressional approval on a piecemeal basis.

Bilateral Reductions: The Act allows for targeted negotiations with individual trading partners, creating a more strategic approach to trade liberalization and giving exporting industries equal status with import-competing industries at the negotiating table.

Most-Favoured-Nation Clause: Tariff reductions negotiated with any one country automatically apply to all countries that have commercial agreements with the United States, creating an expansionary effect and accelerating the process of global trade liberalization.

While the act initially focused on bilateral agreements, it created a template that later informed the international trade architecture.

1947: Bretton Woods and the GATT – rules for a world at war

As World War II ended, the architects of the postwar economic order gathered at a resort in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods would give the name to the system they had designed — a framework designed to prevent the economic nationalism and financial instability that had caused the war.

The Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944 brought together 730 delegates from 44 Allied nations for three weeks of intense negotiations. The meeting reflected two competing visions of the postwar economic order. On one side was British economist John Maynard Keynes, who represented a war-torn Britain now dependent on American financial aid. On the other was Harry Dexter White, who represented the United States, now an economic giant.

Keynes proposed an ambitious plan for an “International Clearing Union” that would have created a global currency (which he called a “bancor”) that would automatically balance trade and prevent excessive surpluses or deficits. White’s plan was more conservative, preserving national monetary sovereignty while establishing a stable exchange rate based on $35 to the dollar for an ounce of gold.

Whites plan largely prevailed, but it also made important concessions to Keyness concerns about flexibility of adjustment. The final agreement established two key institutions: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which monitored exchange rates and provided short-term financing to countries facing balance of payments difficulties, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, now part of the World Bank), which promoted reconstruction and development through long-term loans.

The Bretton Woods system represented a compromise between the rigidity of the pre-1914 gold standard and the chaos of currency wars during the interwar period. Countries would maintain fixed but adjustable exchange rates against the dollar, which served as the system’s anchor through its peg to gold. The IMF would provide short-term financing to countries facing temporary balance of payments problems, allowing them to adjust without immediately resorting to austerity policies or competitive currency devaluations.

The system was designed explicitly to prevent the disastrous economic nationalism of the 1930s. By providing liquidity and aid, the system was intended to give countries breathing room to maintain domestic economic stability and international cooperation. The architects of Bretton Woods knew that the choice between domestic economic goals and international obligations had torn the economic system apart during the interwar period. Crucially, the architects of Bretton Woods recognized that monetary stability alone was not enough.

A complementary trade framework was needed. This was enshrined in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947.

While the United States and Britain agreed on the framework of the system, they disagreed on the core issues. The United States wanted to eliminate Britains imperial system of preferences. Britain wanted the United States to slash tariffs, which had been high since the days of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. What was the compromise? Multilateralization, diluting political influence and dispersing pressure from all sides.

Its core pillars:

Most Favoured Nation (MFN): Every trade preference made to one member country must apply to all member countries.

Tariff Binding: Once tariffs are cut, they cannot be raised without compensation.

Eliminate quotas (mostly): Because nothing says “central planning” more than restrictions on chicken imports.

Over the next few decades, a series of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (Annecy, Torquay, Dillon, Kennedy, Tokyo, Uruguay) gradually reduced global tariffs, transforming the temporary postwar peace into a well-functioning world order. By 1994, when the GATT was renamed the World Trade Organization, the global average tariff had fallen from 22% to below 4%. From the original 23 founding contracting parties, it gradually expanded to include most of the worlds trading countries and witnessed a dramatic expansion of international trade in the postwar decades.

The brilliance of the GATT was its simplicity. It treated tariffs like nuclear weapons: dangerous if used, contagious if retaliated against. The core principle of the GATT was not that all trade was good, but that any retaliatory protectionism was bad. In effect, it was a behavioral contract: No more weaponized tariffs. No more trade collapse. If you want to raise barriers, you pay. If you make a deal, you share.

That’s why the GATT was surprisingly durable. It worked for decades for a simple reason: when it failed, everyone remembered what happened.

However, the Bretton Woods monetary system proved to be less resilient. Faced with persistent balance of payments deficits and declining gold reserves, President Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold in August 1971, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates.

1971: End of dollar-gold convertibility

Gold and silver were widely used as currencies for international trade settlement from the Age of Exploration to the Colonial Era (roughly 1400 to the mid-1900s). In particular, the Spanish silver dollar was most commonly used for international trade settlement (the word dollar is derived from silver mines). In general, a fiat currency system based on IOUs may work well locally (trust and enforcement are feasible), but it does not work internationally.

For example, during the Golden Age of Piracy, the Caribbean was a melting pot of European colonial empires (British, French, and Dutch), all of which used Spanish silver dollars for trade settlement. The Spanish Empire was the largest source of silver and minted standardized, ubiquitous silver coins. Even on the other side of the world, China would only accept silver (specifically Spanish silver dollars) in exchange for the tea it sold to Britain.

During the period when the British pound (backed by gold) was the dominant reserve currency, the United States became the world’s largest economy during the American Industrial Revolution in the late 19th century and became a recognized military superpower in 1944. After 1971, the US dollar became the first true legal global reserve currency. It can be understood as follows: the US dollar became and continues to be the dominant global reserve currency under the network effect of winner-takes-all.

It is not difficult to understand the impact this has on the US economy:

Given that gold and silver deposits are spread all over the world, even the monetary system of the Bretton Woods system meant that no single country was the sole source of global reserve assets. Under the Bretton Woods system (1944-1971), national currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, which was redeemable for gold at a fixed rate. Thus, in addition to gold itself, the British pound and the Swiss franc were functional substitutes for reserve assets.

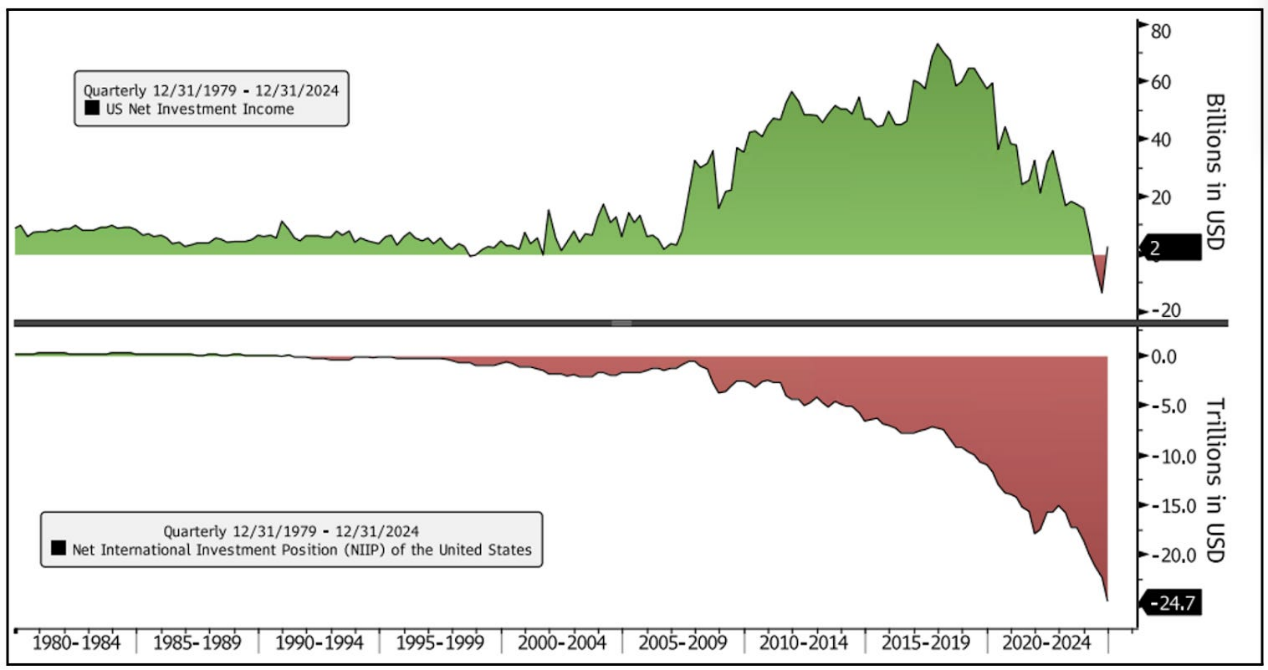

Somewhat surprisingly, the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 served to cement the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. As the source of the only major reserve currency, the United States ended up in a dynamic of running a persistent trade deficit in order to provide a liquid reserve asset to the rest of the world. This seemed perverse because initially the dollar was being abandoned in favor of the “real” thing — gold. In the 1980s, Volcker reestablished the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. In 1980, gold was no longer a one-way bet against the dollar. It was “revealed” as an unstable commodity subject to speculative booms and busts — not a stable store of purchasing power. Since the 1980s, the United States has struggled to run a trade surplus (given the natural tendency of the rest of the world to accumulate financial wealth denominated in reserve currencies).

However, the dollar’s reserve currency status is not without benefits to the U.S. The concept of “exorbitant privilege” means that, despite the rest of the world owning more U.S. assets than the U.S. owns in the rest of the world, the U.S. actually earns more from its overseas investments. This is because a large portion of the U.S.’s overseas holdings are in the form of high-quality, low-yielding U.S. dollar currency balances and fixed-income securities (e.g., U.S. Treasuries, agency MBS, etc.).

While an IOU-style legal system can work globally when international trust and enforcement exist (and it has for decades), the global order of American hegemony is now being questioned—not by the rest of the world, but by the United States itself.

How will the future develop?

While the world has changed dramatically since the post-World War II era of reciprocity, the fundamental contradictions that have shaped America’s tariff history remain. Today is at the same inflection point that changed trade policy in 1930, 1947, and 1971. Just as those inflection points were driven by shifts in America’s place in the global order, today’s tariff resurgence reflects another realignment of economic power. There is a key difference, however: America is actively disrupting the system it built.

This crisis will not be over in three months.

Everything the United States does over the next three months, instead of reducing the burden of trade or returning to a reasonable model (such as a 10% across-the-board tariff and targeted reciprocity), will be the first shot. The focus will be on isolating China and trying to force it to the negotiating table. If you are not with us, you are against us.

There are 2-3 months worth of inventory sitting in US domestic warehouses, which is enough to offset or distort the initial impact of the global trade disruption. As these inventories run dry, the true impact of the global trade freeze and its aftermath will begin to be seen. Reserve managers will continue to reduce their investments in the US dollar as it enters a secular bear market.

The suspension of tariffs is a tactical gesture in the ongoing negotiations. It is unlikely that the US will reach a permanent solution with China in the next 2-3 months, but some indirect progress may be made in trade negotiations with Europe and even Latin American countries. The market interprets this as a move to ease tensions, but the reality is that it has increased uncertainty in the business environment. In order to survive the next 90 days, it is necessary to be clear...

How to understand the government’s views?

In this context, it would be helpful to understand the government’s view. In Trump’s view, the US hegemony and reserve currency status is an unfair treatment for the US - not only has it lost advantages in trade and manufacturing, but it is also maintaining the global trade system for “free”. Therefore, the US position can now be roughly summarized as follows:

What’s really weird isn’t the use of tariffs. There’s nothing weird about that. Trump has been a tariff fanatic for decades, and if you’re surprised that “Tariff Man” is imposing tariffs, you’d better look elsewhere.

Surprisingly, these three Rs returned at the same time, but still failed to show the full picture.

Revenue, in the form of billions in new federal revenue, was not called a tax increase, but it was essentially the same as one.

Restrictions are not just an industrial strategy but a populist aesthetic – a wall, built at ports rather than borders, applied to everything.

Reciprocity has changed from mutual relaxation of barriers to a showdown of grudges calculated based on trade deficits.

There are other factors at play that are not simply revenue issues, but are unique to this approach and the globalized world in which it occurs. An R needs to be added to define the change that this seemingly simple tariff rate increase represents. Because we are not really returning to the dynamics of the past, but we are entering a completely new situation.

To do this, it is essential to fully understand the government’s perspective. We wrote about the challenges of trying to rebalance global trade by targeting other countries’ deficits in our article “Seeing the Stag” two weeks ago. The “Triffin Dilemma” describes the paradox facing a reserve currency country (which existed before the end of the dollar’s convertibility into gold). The paradox is as follows:

“It is too much for one country and one currency to provide the world with reserve and exchange services.” Henry H. Fowler (U.S. Secretary of the Treasury)

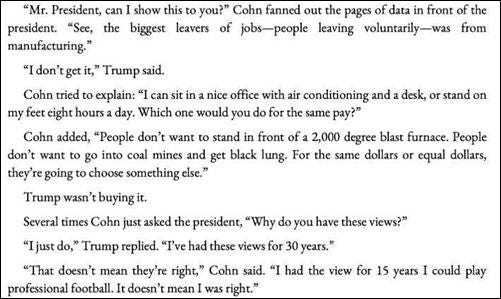

Unsurprisingly, the Trump administration’s interpretation of the Triffin Dilemma is more about bills than IMF white papers. They believe the United States has been taken advantage of and forced to run a trade surplus, and they want to correct that. By imposing tariffs on countries’ trade deficits, it’s a good indication of where their priorities and concerns lie.

From the Trump administration’s perspective, what has happened/is happening in the existing system is:

Foreign central banks buy dollars not out of preference but out of obligation - because if you want to keep your currency lower and increase exports, you need to hoard dollars.

Those dollars are deposited into U.S. Treasuries, which happens to fund the same U.S. government that complains about being taken advantage of.

The dollar remains structurally overvalued, a direct consequence of its role as the savings account and lifeboat for everyone else.

American manufacturing has been hollowed out not because China cheated but because the United States played the role of system administrator in a network it did not fully control.

Eventually, the trade deficit grew, and Trump disliked the word “deficit” or the idea of being the world’s largest “debtor nation.” The role of a reserve currency began to be seen as a liability, not a privilege.

From this perspective, tariffs are not just about protecting factories or funding governments. They are overdue expenses for maintaining the system. In effect, they are like the geopolitical equivalent of “rent” — the $14.99 per month you forgot you subscribed to. More simply, the government’s view is:

“We manage the system — regulating flows, securing waterways, buying your exports, issuing your reserve assets. Now we’re charging you.”

The Fourth R: Rent

Rent redefines tariffs as a fee-for-service model of global economic participation rather than a means to finance states (revenue), protect domestic producers (restrictions), or ensure mutually beneficial access (reciprocity). This new model is essentially…

Globalization as a Service

Tariffs, NATO threats, opposition to foreign takeovers, etc., are forming a deliberate pattern: using all available means to extract national wealth from foreign dependent countries, even if such means undermine global trade and the dollars status as a reserve asset.

Tariffs are a blunt tool, and Trump is clearly using them as part of a broader negotiation to try to upend the system. The 125% tariff on China is the most obvious example. Tariffs this high will disrupt trade. So why not use sanctions or quotas? Because it is critical to start negotiations from the perspective of paying the bill.

There are a number of possible outcomes to the negotiations for the 90-day tariff suspension. The main focus will be on building a coalition to force China to the negotiating table, but we may also start to see discussions about imposing this “fee” in a more permanent way.

How to pay the rent?

I have always been skeptical of the idea of a Mar-a-Lago deal, and it is highly unlikely to come to fruition. However, the discussion is still valuable. The proposed 100-year bond may have unintended negative consequences, but it is a great example of how the fourth “R” (rent) works.

The idea is that by issuing 100-year bonds with negative real interest rates and encouraging (forcing) countries to swap their existing long-term bonds for newly issued bonds, the United States can gain additional economic benefits from continuing to maintain its status as the worlds reserve currency and a facilitator of global trade.

Although the impact is unpredictable and potentially messy, damaging U.S. creditworthiness and significantly disrupting the yield curve, Trump would likely be keen to eliminate tariffs (or significantly reduce them) for countries that agree to convert their Treasuries into 100-year bonds with negative real interest rates. After all, he has spent his life restructuring and refinancing debt for various Trump agencies.

This is just one example, and an unlikely one. Stephen Milan recently said he is not advocating this idea. But the fact is that Trump is launching an attack on the existing international rules of the game and questioning the role of the dollar and US Treasuries. Why? Because he is only focused on the impact of the current situation on US finances. This view risks missing the forest for the trees.

If the US actually defaults on foreign holdings of Treasury bonds in a hostile Century Bond issue/swap, this could cause gold prices to rise and the dollar to fall. The impact on the yield curve would be dramatic. Even if this does not happen, it seems likely that official foreign exchange reserve assets will further diversify towards gold, euros, francs and yen. And, there is the possibility of an agreement to settle trade in currencies other than the dollar.

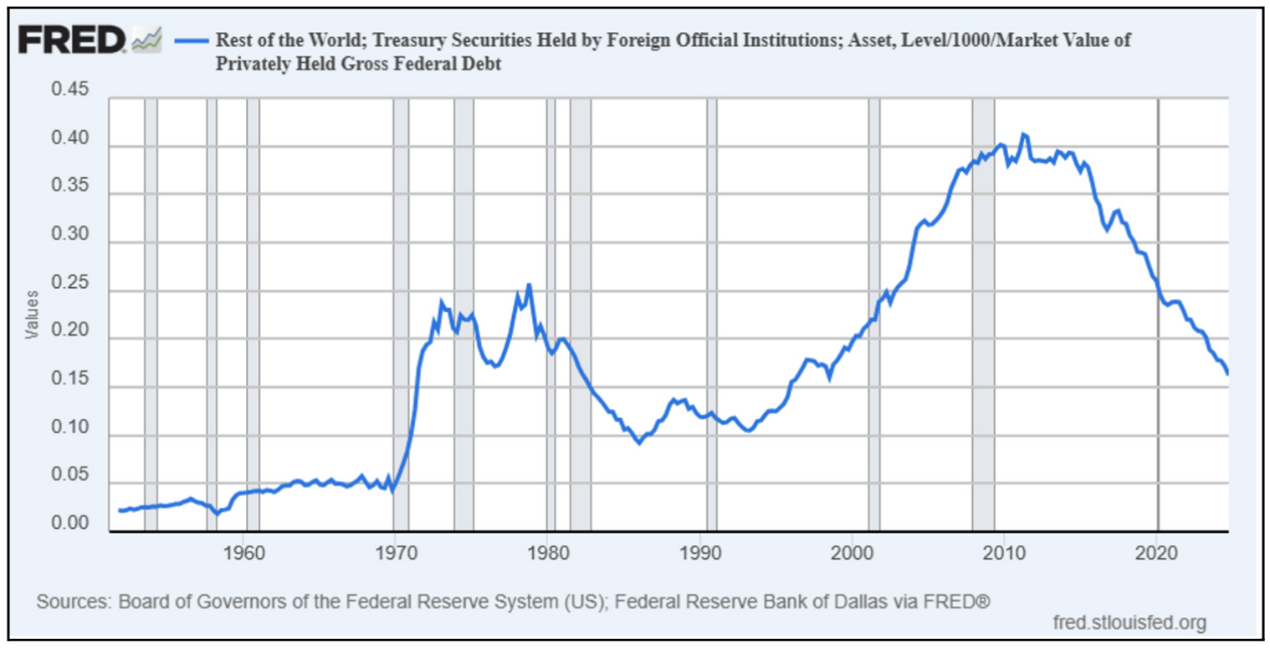

Given this underlying reality, it’s no surprise that official holdings of U.S. Treasuries have been declining for years:

Current U.S. policy could easily be viewed by other countries as extortion. This kind of economic brinkmanship is inherently risky. If it fails, it would be like the U.S. being both the bank and the customer, taking a loan from the bank… and then deciding to default on it.

But the fact remains: countries are currently negotiating with a man who is ready to destroy the entire system, no matter what the consequences. It is not hard to see how many countries would rather succumb than face the world and difficulties of deglobalization.

Will this scenario have an outcome that will not severely damage the global economy? Yes, but it will not have an outcome that will quickly restore global trust in the United States.

Regardless of how the negotiations progress, it is clear that trade policy will be the main driver of cross-asset returns and economic growth this year. It is clear that we are witnessing a regime change that will have macroeconomic consequences for years to come.

In this new system, tariffs are more about precedent than policy. The United States has shown that it will use market access as a regulator, tightening or loosening trade conditions based on geopolitical deference rather than economic efficiency. Whether the administration proposes large-scale tax cuts or other supportive measures will ultimately depend on how quickly and how the U.S.-China trade talks progress.

Nothing could be more important right now. China and the United States have already experienced a rapid spiral of retaliation from the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, reaching as high as 145%.

So even if the circumstances and environment are very different, it’s not hard to understand how those desperate economists and bankers felt in 1930 as they watched the Smoot-Hawley trade war unfold. Globalization has become a bit like economic mutual destruction. There may be “winners.” Maybe one country is only 80% destroyed, while the rest are completely wiped out. But is this really the world we want to live in?

Unlike the Hoover administration, the Trump administration faces the paradox of being both a debtor nation and a trade restrictor. While both have tried to maintain America’s position through tariffs, despite warnings from economists, Hoover’s policies were primarily defensive (and misguided) measures to protect American industry, while today’s approach includes an additional offensive element: deliberately using America’s debtor status as leverage to transform the global trade and financial system from a public good into a private toll road.

While it might be tempting to go back to the last time tariffs were this high and say, “Well, this might happen again,” there are problems with doing so.

The Return of the Tariff Nation?

This is not the 1890s or the 1930s. The world is globalized, integrated, and has never tried to separate again.

We are not far from an event that has brought home to us how interconnected our world has become. The pandemic has not only disrupted, it has revealed. It has shown us in starkly vivid terms how fragile the architecture of global trade has become. Ships have stopped, semiconductors have disappeared, and the illusion of a strong supply chain has been shattered.

I don’t think we can just… dismantle supply chains. I also don’t think the United States can use tariffs to get out of a just-in-time, local, and barely resilient system that took decades to design. Trump’s trade policy is not Smoot-Hawley, although many people try to compare it to it.

I don’t think we can…dismantle supply chains easily. I also don’t think the United States can use tariffs to get out of a system that was designed for decades to be instant, in-place, and virtually inelastic. Trump’s trade policy is not Smoot-Hawley, no matter how many people try to compare it to Smoot-Hawley.

The most disturbing thing about this is that there is no historical frame of reference. You can draw on the 1970s, the 1930s, and any number of other events that reshaped the underlying architecture of the system, but that doesnt explain everything.

The world did not deglobalize in the 1930s because globalization was still low. Today, for the first time, we are witnessing a superpower actively inserting a stick into the spokes of the wheel of globalization that it had built.

Here’s the thing: it might work. Just temporarily, politically. Until it doesn’t.

Just like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was in effect for about three months — until Canada retaliated, Europe re-imposed tariffs, and global trade got caught in a trap, while American farmers went bankrupt in record numbers and still voted for those who kept their agricultural prices down.

Today’s tariffs are different in form but the same in function. They are all based on the same belief that stability can be achieved by destroying complexity. Unfortunately, complexity does not yield easily.

Let’s be frank: No one fully understands how our complex, ever-changing global system works in real time. Not the Fed, not CEOs, not the IMF, and certainly not you or me. The ripple effects are simply incomprehensible. And yet, at our current pace, our collective understanding of it seems only likely to improve in the most disturbing ways.

This leads to a straightforward question:

How can a company commit to a 30-year, capital-intensive investment in a world where the rules can change next quarter?

In a climate where tariffs are not policy but depend on the next tweet, the next election, the next wave of populism?

This is not just a trade problem, it is a capital formation problem. Long-term investment is possible only under a very rare combination of conditions: predictability and trust in institutions are the two most important ones.

While U.S. markets have been remarkably resilient through world wars, the Great Depression, stagflation, the tech bubble, and bank runs, that resilience is no accident. It is built on a rare and volatile combination of ingredients that most countries cannot assemble, let alone maintain for decades.

First is global trade. For nearly a century, the United States has been a central node in the worlds commercial network—not because it produces the cheapest goods, but because it offers the deepest markets, the most trusted currency, and the broadest consumer base. Trade has been the unsung hero of American prosperity, enabling the United States to import low-cost goods, export high-value-added services, and convert global surpluses into domestic assets.

The second is political stability. Whatever one says about the polarization and absurdities of the two-party system, the peaceful transfer of power every four years and the predictable continuation of contracts, courts, and governance give capital the confidence to stay. Investors may hate regulation, but they hate chaos even more.

Add to that a robust legal and regulatory framework. Property rights. Bankruptcy courts. Enforceable contracts. These are the boring technicalities of capitalism, but without them, capital cannot flow.

Then there is the dollar, of course. America’s reserve currency status creates a gravitational field for global capital. Foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, multinational corporations: they all hold dollar reserves, settle transactions in dollars, and manage risk in dollars. This demand drives down America’s borrowing costs and gives it an unparalleled ability to run deficits without immediate consequences.

Finally, there was luck. Two oceans, a network of rivers and navigable waterways, natural harbors, excellent agricultural conditions, and no hostile neighbors for a century and a half. Abundant natural resources. A population boom at the most critical time. An internal market the size of a continent. If you were to design a country destined for hegemony, the American map would be the best blueprint. The United States was lucky, to say the least.

The system appears solid on the surface, but is in fact a maze of interdependent processes—a balance held together by geopolitical inevitabilities, norms, incentives, and a polite collective delusion that tomorrow will be roughly like today. Only geopolitical events that massively adjust the architecture of the system lead to prolonged volatility, without “buy the dip” moments—1971 being a classic example.

Back to the fundamental question, the answer to this question will soon be found.

What is the cost of unpredictability?

What is the cost of unpredictability? Honestly, I don’t know. I don’t think anyone knows. But there is a limit to what the system can take, and once it is crossed, it cannot be reversed. Perhaps the good news is that the United States still has more influence than any other country in the world. Unless other countries unite, though, or are willing to endure more pain than the Trump administration expects.