8000 words explain the periodicity and negative feedback cycle of the public chain fee

This article comes fromMedium, the original author: Nic Carter, compiled by Odaily translator Katie Ku.

This article comes from

, the original author: Nic Carter, compiled by Odaily translator Katie Ku.Watt invented the centrifugal governor in 1788, a small and ingenious device. With this device, the steam engine was made practical in the industrial field. The centrifugal governor takes the high efficiency cycle input from the steam engine and applies it to the weighted balls. As they spin, centrifugal force pushes them up, which moves a lever attached to the valve. When they spin faster, the valves close. In this way, the governor takes input from the steam engine and mechanically regulates the steam flow and thus the speed of the engine.As the energy of the system increases, a negative feedback loop forms, limiting its growth.

For a steam engine, this is part of its design. As we will see, a similar phenomenon exists in public blockchains, but with more complex results.

secondary title

Strange Case of Periodic Fees

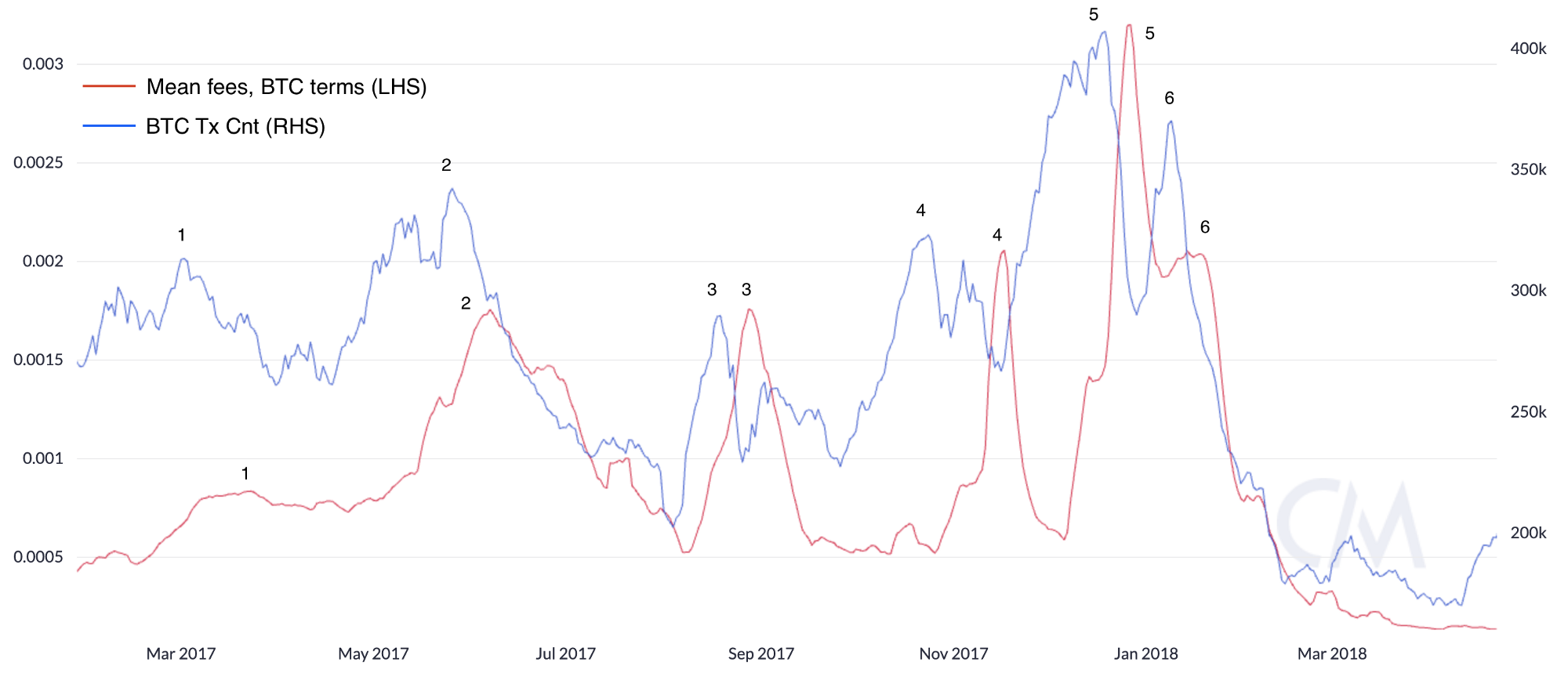

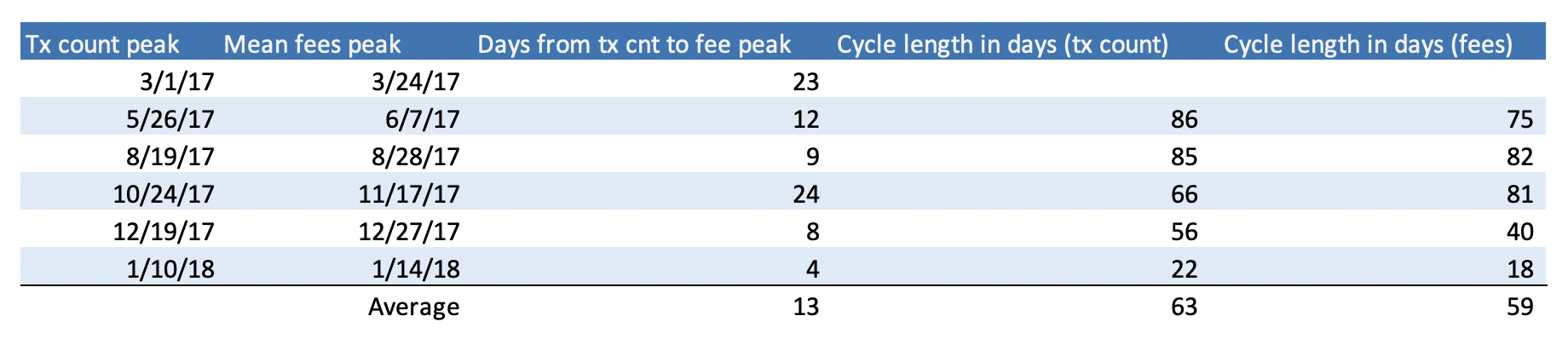

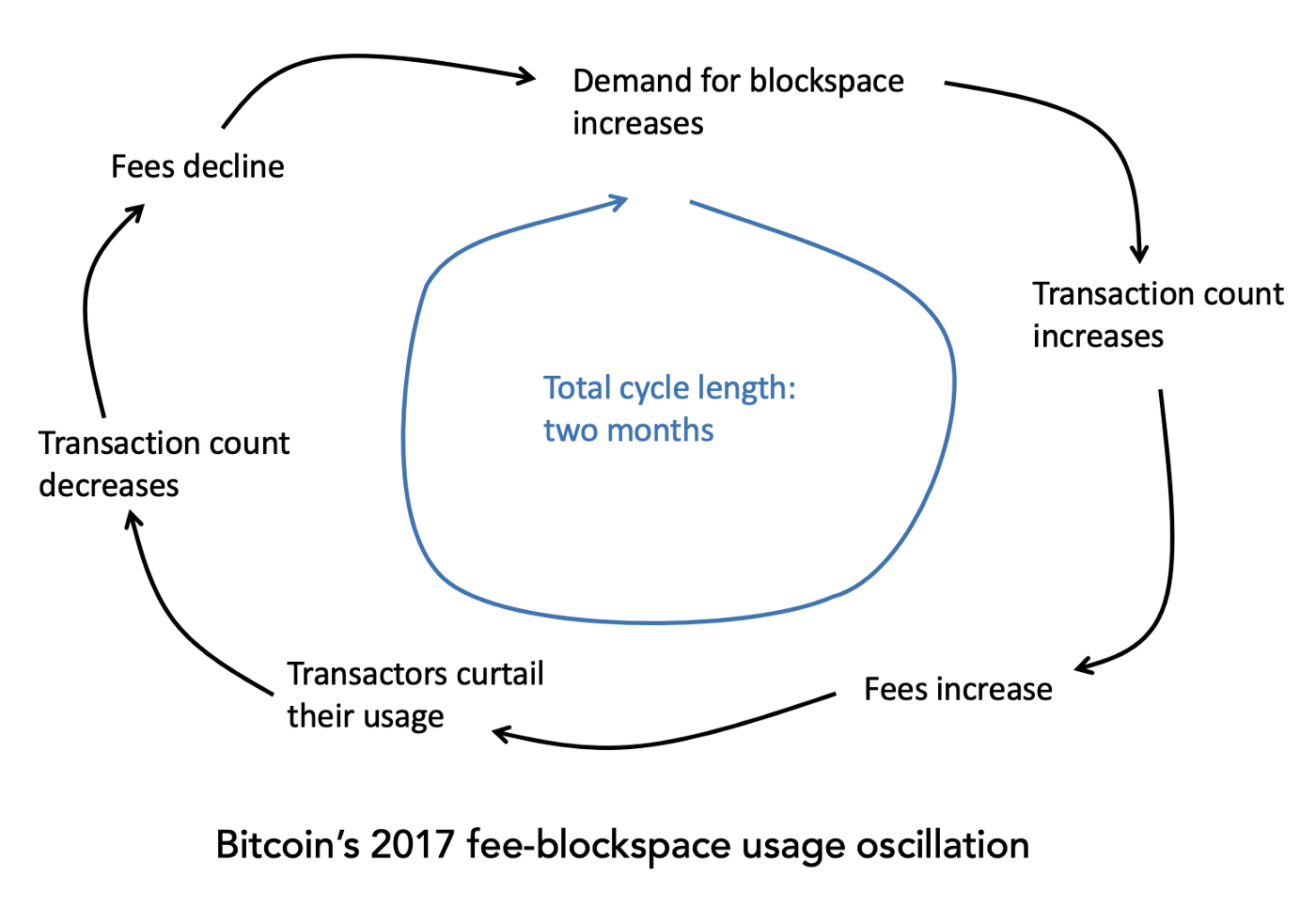

As the market frenzy of 2017 subsided, I noticed what seemed to be a recurring pattern in Bitcoin’s fees and transaction volume. Blocks will fill up, fees will skyrocket, transaction volume will start to drop, and then blocks will fill up again. According to my analysis, this cycle repeated six times in 2017.

Note that I have smoothed the average fee and number of trades to the 7-day moving average. People dismissed Bitcoin’s late 2017 “fee crisis” as a simple event, but there were actually at least four periods of sharp fee increases, or six periods if you count smaller peaks. It's just that most people calculate their fees in dollars rather than local units, so they don't really notice the eventual fee spike when Bitcoin's dollar value also spikes.

On average, fees peak about two weeks after a transaction is completed. The entire cycle took two months to complete, although it has been rising throughout the year. As blocks gradually fill up, new small amounts of transactions push fees beyond acceptable limits for traders. Of course, fees are just a phenomenon, and the underlying problem is actually block space.

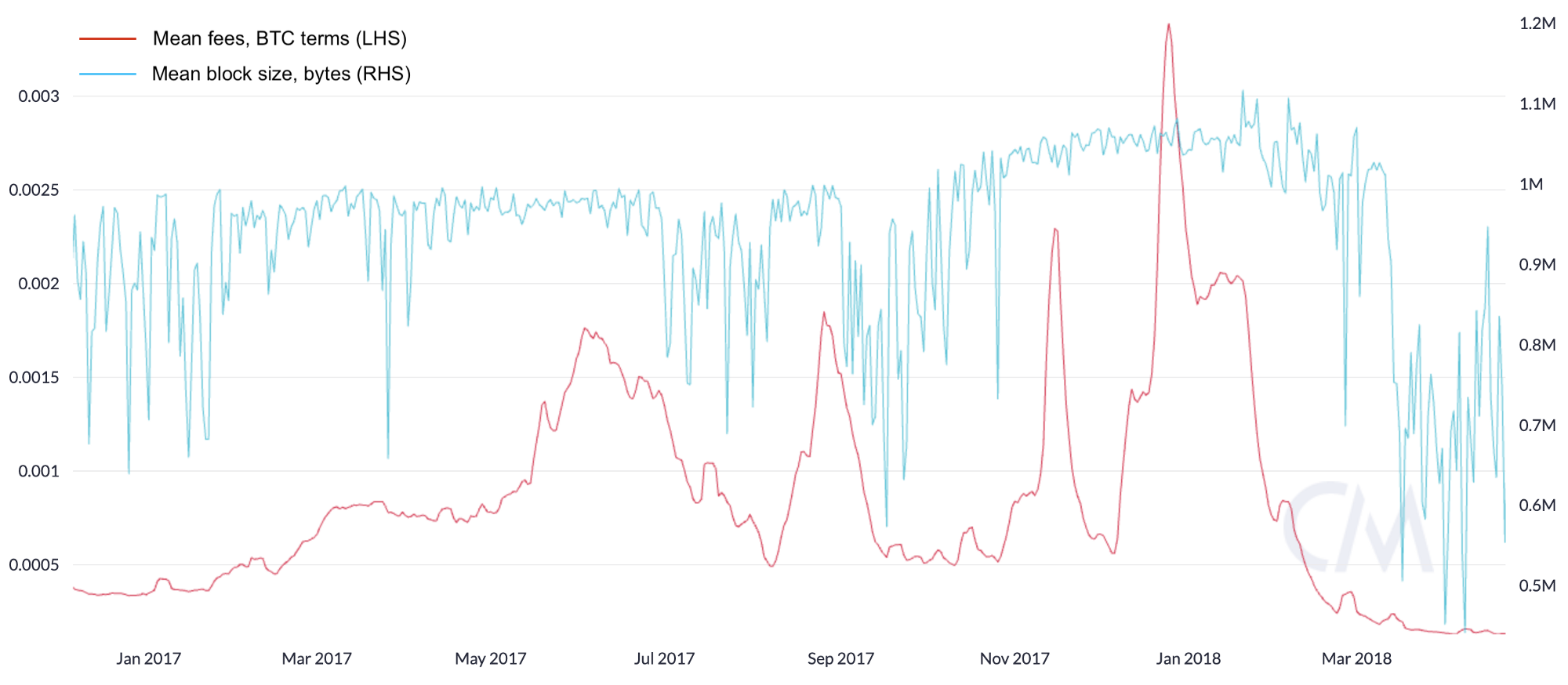

You can visualize the development by examining the relationship between block filling and average fees.

Using this method, you can see the fees gradually go up as the blocks are filled and the limit is reached. As fees peaked, users opted to reduce transactions and empty blocks, resulting in variable block sizes. But as fees fall, block space looks more attractive to users, and users will almost come back to the protocol again, causing blocks to fill up again. During the last fee spike around January 2018, both the price of BTC and USD, blocks were maxed out and continued for months, with fees reaching staggering levels.

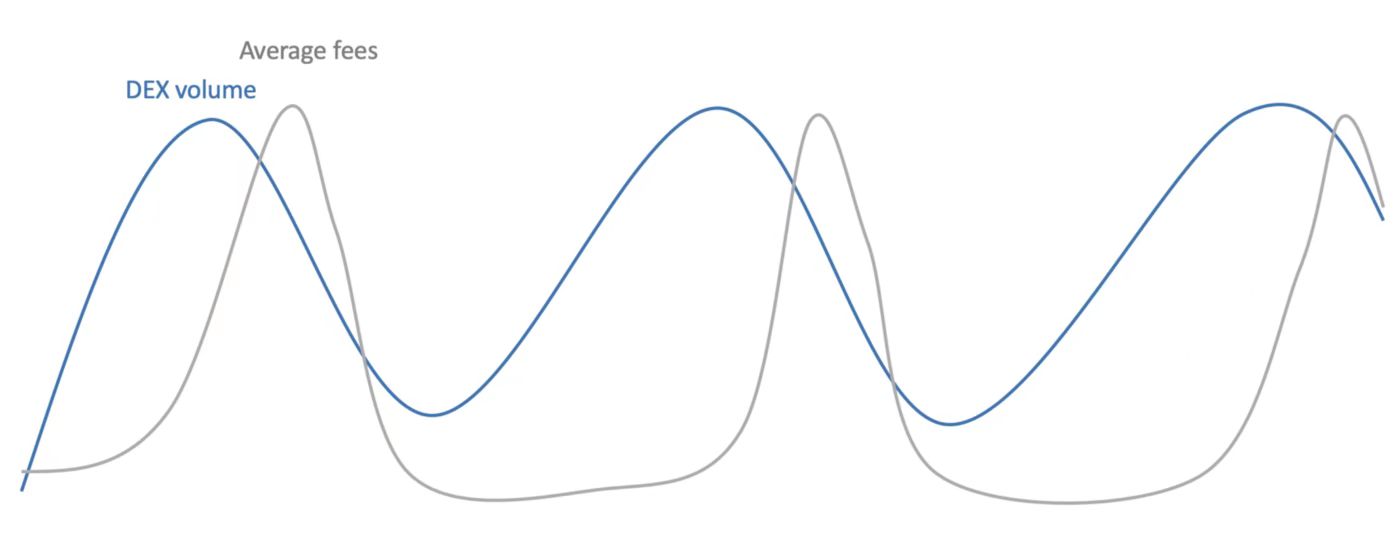

Here is the process diagram. I call it a wave graph because this causes fees and blockchain resource utilization to fluctuate like a sine wave. But you could also describe it as a negative feedback loop, as fees inhibit transactions when they reach a certain threshold.

This was just my curiosity, I pointed it out at the time, but it doesn't really have much to do with cycles. You have no way of guessing what the number of transactions will be in a week. The lesson I learned from this is simple: At some point, users get frustrated with fees and deprioritize on-chain transactions, especially if the fees are large relative to their transaction size. SegWit offers quite a bit of help. From a certain point of view, fees are self-adjusting, because they encourage large consumers of block space to save some chain resources. However, all of this makes me more certain that a Bitcoin fork will require a lot of delayed transaction systems that need to be added to BTC under a range of trusted models. Another takeaway for me is that users have demonstrated to us a clear transaction cycle and after a period of high fee pressure, it takes weeks to return to previous transaction levels.

secondary title

Ethereum's 2020 "fee crisis"

This year, when Ethereum fees began to climb and eventually surpassed Bitcoin fees, I wondered if Ethereum would see Bitcoin’s fee dynamics replicate. I'm confused as to whether it would have the same impact or be more disruptive on Ethereum since so much liquidity is "on-chain" (as opposed to being mostly off-chain on exchanges). In my opinion, Ethereum's supply of block space is dynamic and can increase as usage increases. As it turns out, the fees ended up being more disruptive than I expected.

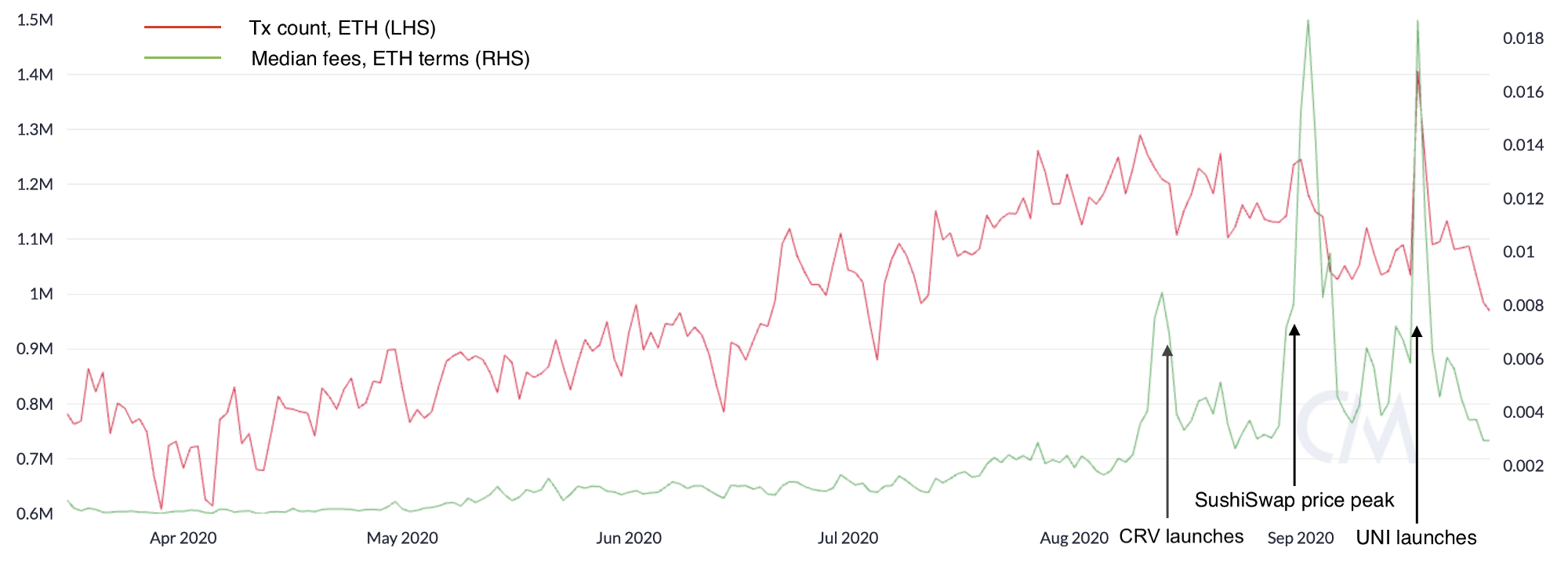

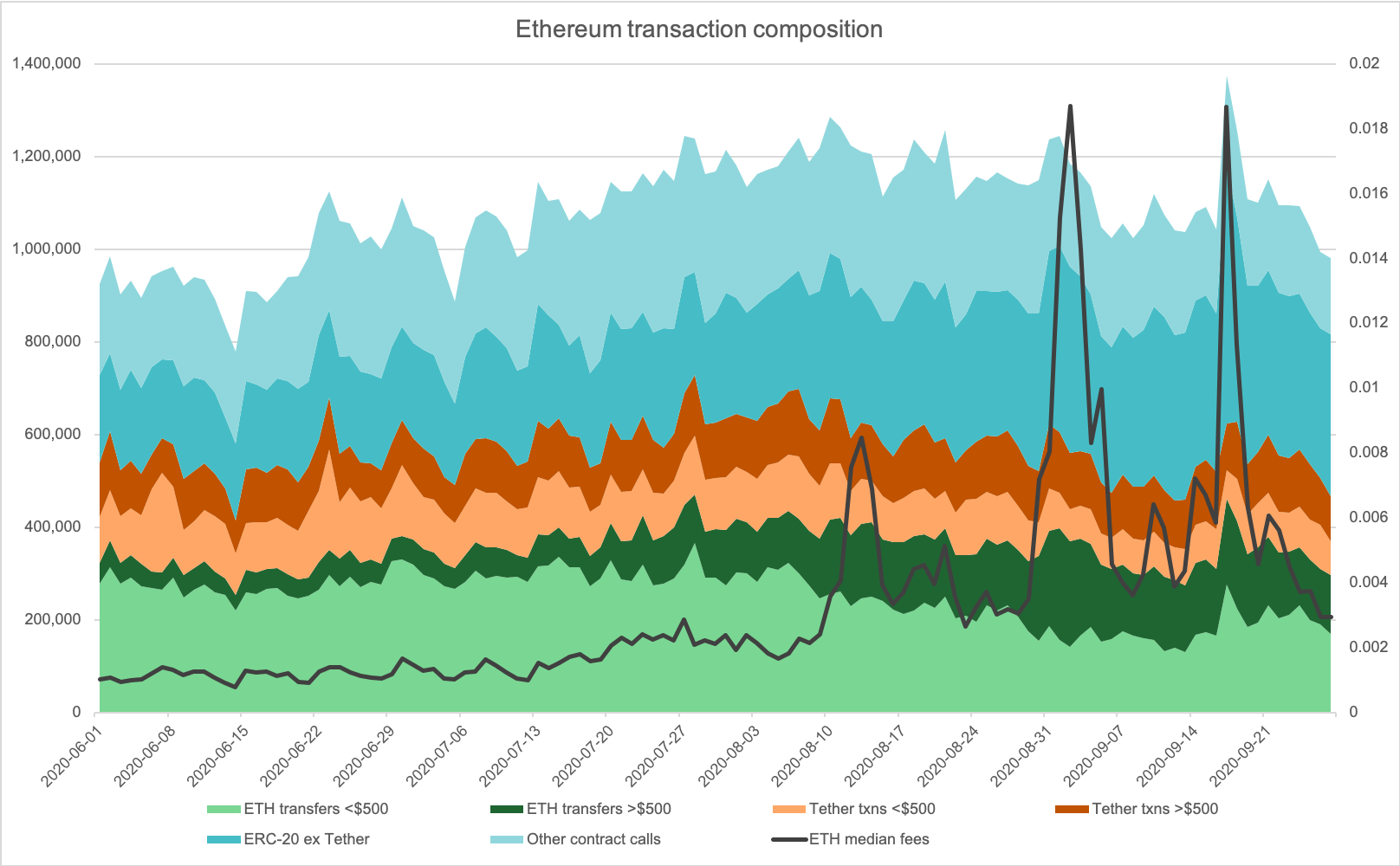

Like Bitcoin in 2017, this year’s Ethereum saw a surge in utilization as transaction volumes grew, gradually increasing fees. The token launched by Compound in mid-June intensified the utilization rate of the blockchain, thereby increasing the pressure on handling fees. Since mid-August, many other products have been launched and the handling fees have reached a state of gradual increase. The dual issuance of tokens from SushiSwap and Uniswap are a couple of notable events. On September 2, the average transaction cost on Ethereum exceeded $14. Overall, $16.7 million in ETH fees were paid out that day, far exceeding the $5.98 million in miner revenue for new issuance. As these fees increased, some users chose to defer transactions, and the number of transactions began to decline. As we entered a new period of high fees in mid-August, Ethereum’s daily transaction volume began to decline steadily. Fees peaked late on Sept. 2, but also started to drop in the last month.

Two days later, on September 4th, I predicted on the On The Brink podcast that Ethereum’s high fees would not only affect the utility of the chain, but also the liquidity of decentralized exchanges. Here's a short excerpt from the podcast:

Nic: We saw fee-tx count fluctuations in Bitcoin in 2017, and I predict the same will happen in Ethereum. It is very obvious that the transaction fee increases with the increase of block space utilization, and at a certain critical threshold, users start to be unacceptable and stop transactions for a period of time. This is an economically unfavorable deal for them. So the number of transactions and the fees go down, and then the fees get cheaper, so people can transact again, and the cycle continues.

And I think if you look at the sell-off, that might also be related because some of the retail investors who are using the on-chain exchanges are pricing out of those trades. And, without retail investors, smart traders have a lot of uninformed trading liquidity to gamble with. So I think generally, it's a hit to liquidity.

Matt: Without individual investors, there is no collective.

Also, while ETH price dynamics are difficult to ascertain, I'm not saying they're entirely caused by this phenomenon, but ETH and USD peaked on September 1st and then dropped from there, while fees remained the same throughout the rest of the month keep going up.

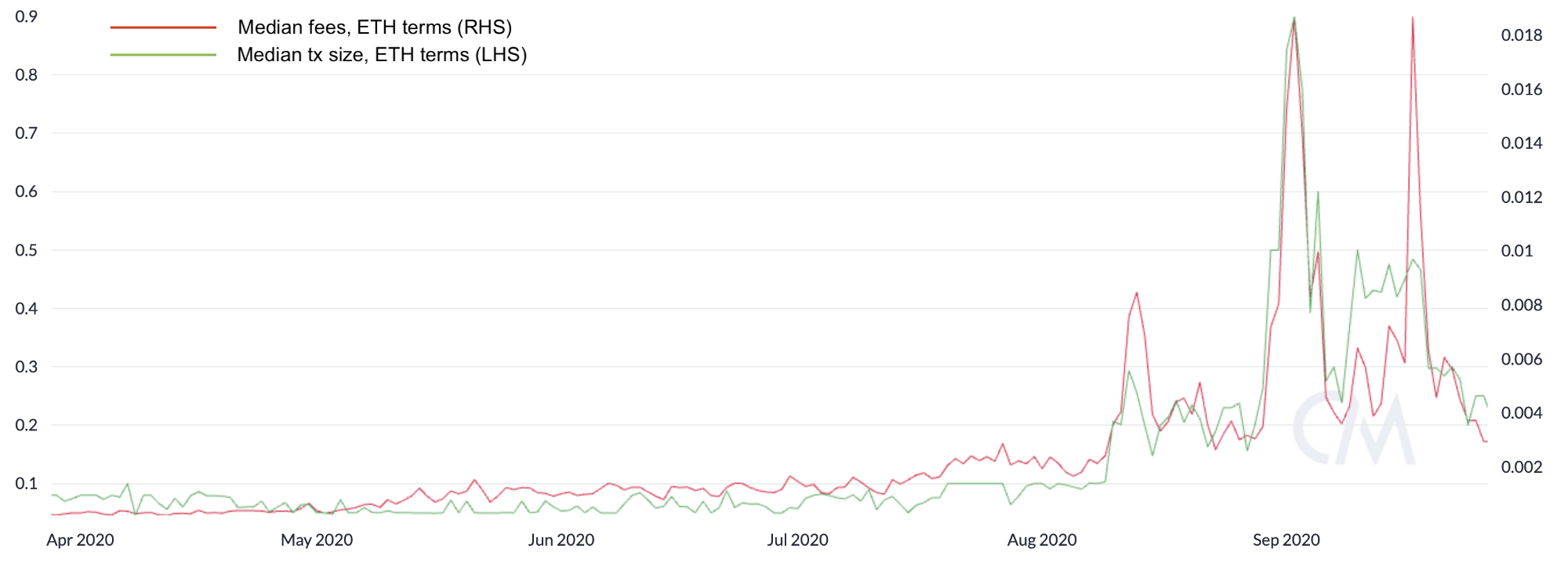

So what's going on? First, Ethereum entered what I believe will be its first major period of fee on-chain usage volatility, with fees peaking about three weeks after transactions were counted and then both falling. Even more interestingly, the average size of Ethereum transactions, as well as various stablecoin transactions, spiked as fees rose. This makes sense, users can see how much they are willing to pay in fees (as a percentage of transactions), and as fees increase, they stop making small transactions and larger traders start to dominate.

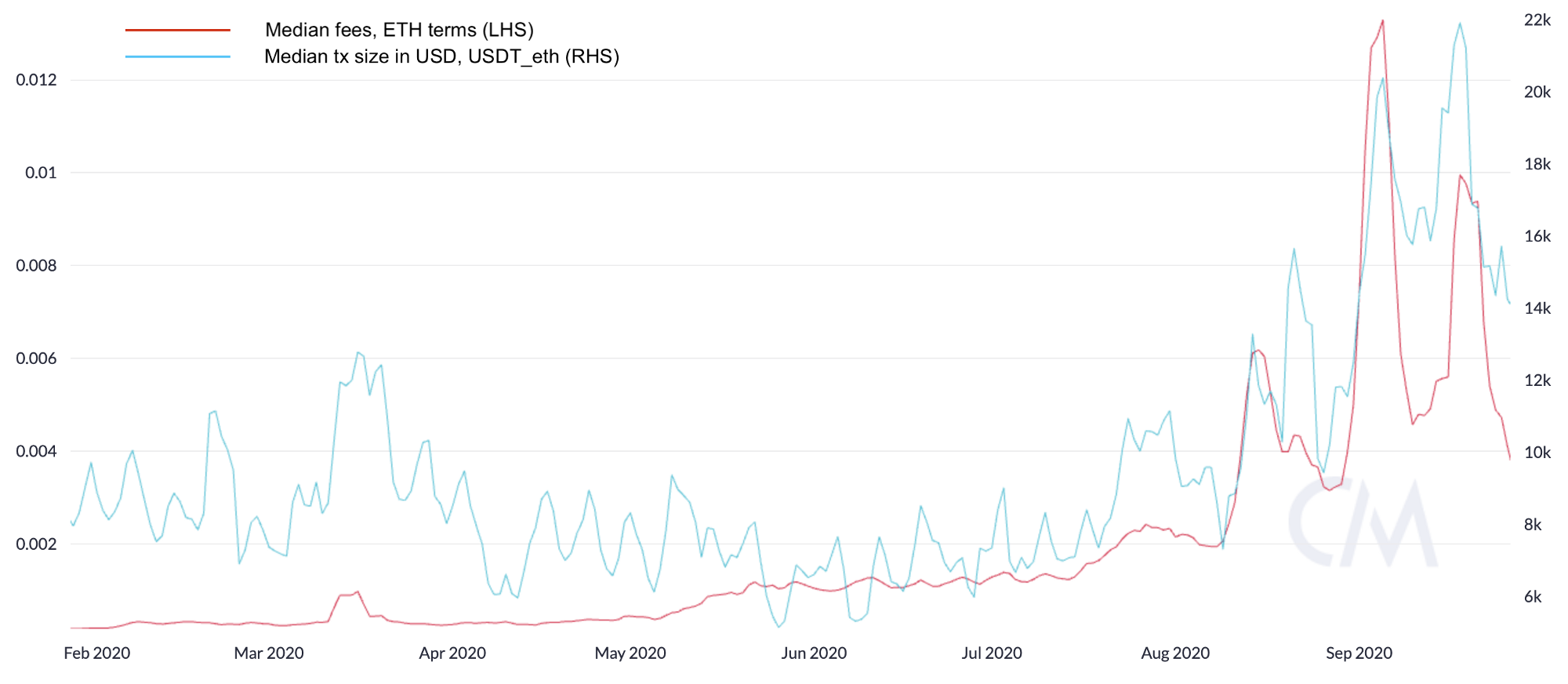

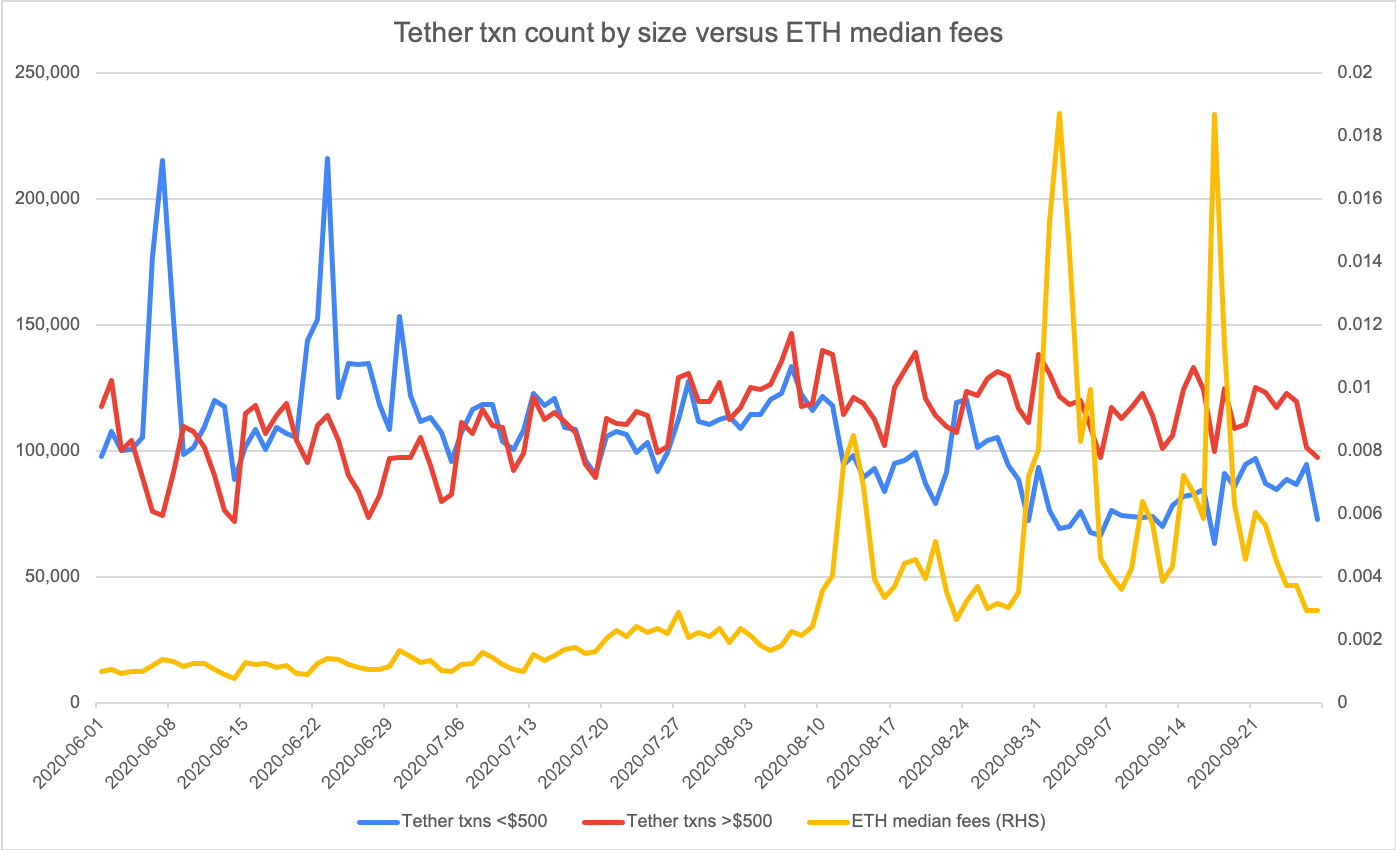

Not only that, but basic ether transactions also exhibit this fee sensitivity. As ETH fees increase, tokens like Tether also demonstrate an increase in transaction size.

This suggests that traders have a fee threshold, a percentage of the transaction amount they are willing to pay, and as fees increase, they become reluctant to make smaller transactions unless they really have to.

The above can be explained by a third explanatory variable, such as the growth of liquidity mining, which both clogs the chain and leads to larger trader entry. I learned more when I investigated what constitutes an ether transaction. I had a hunch that traders with small assets were pricing in fees, but I didn't know until I put together this graph.

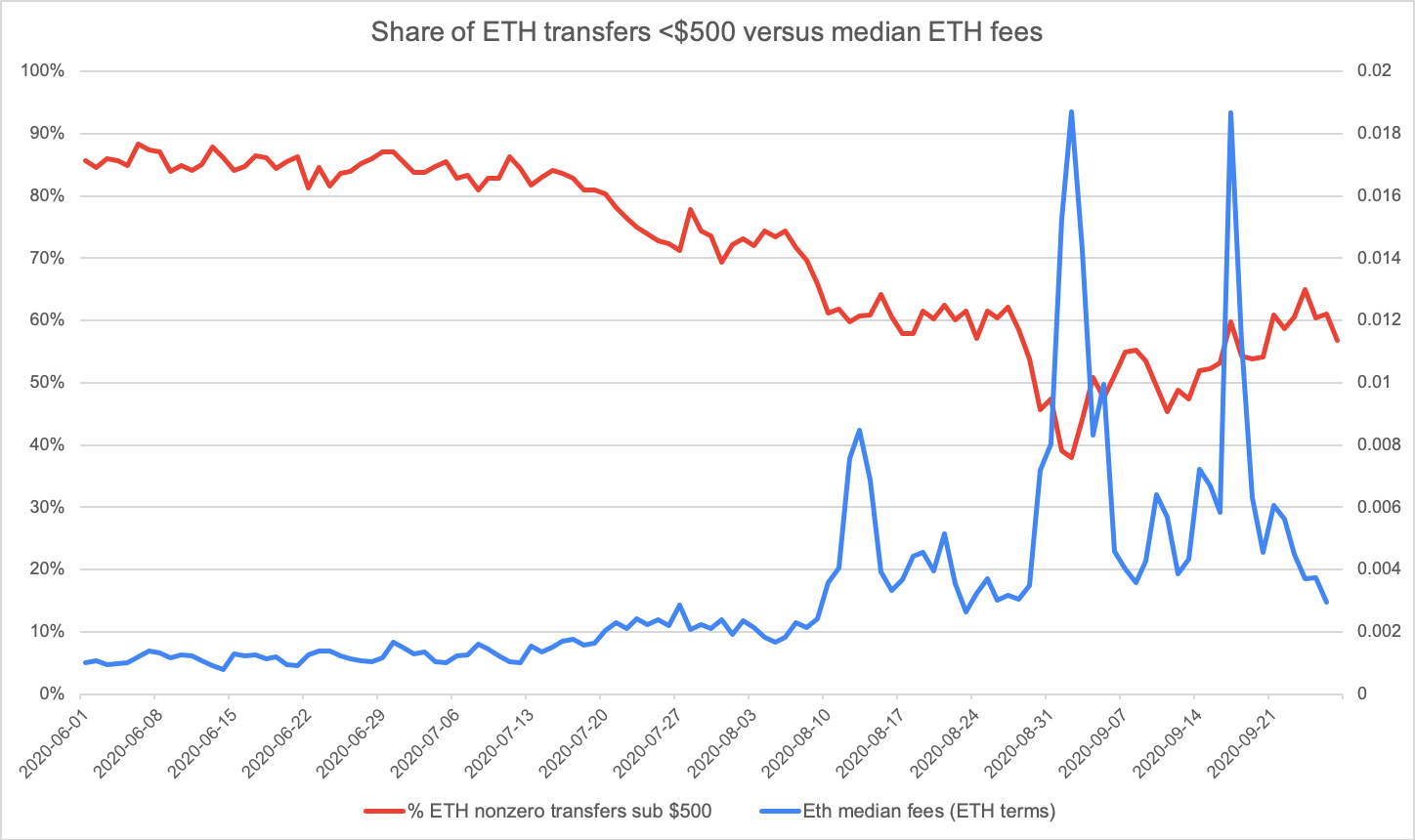

For off-contract bullish trades, around 85% of June ETH transfers below $500 were unchanged, but they fell to 40% when fees spiked. Finally, there is some hard evidence that supports my hunch that fees benefit smaller users.

Predictably, the same phenomenon exists in the usage of the largest ERC20 token, Tether. As median fees began to climb in mid-August, smaller USDT transactions began to decline. Larger Tether transactions held firm, but still showed an overall trend down, as transactions leveled off during periods of high fees.

secondary title

Will high handling fees affect liquidity?

Thus, we have established that there is a clear negative feedback loop between fees and blockchain resource utilization in both Bitcoin and Ethereum. In Bitcoin, we know that this cycle has historically taken two months to complete. We have yet to see what Ethereum will look like. Furthermore, it is clear that traders have a threshold for maximum acceptable fees relative to the size of the trades they are making, and smaller traders put off trading during periods of high fees. This causes the average transaction size of ETH and other tokens to gradually climb during periods of high fees.

In 2017, bitcoin transactions were conducted on centralized exchanges, and the blockchain was used for inter-exchange settlements as well as user deposits and withdrawals. The actual market is off-chain. Users can fund exchange accounts with fiat currency and hold (and then sell) bitcoin without actually touching the blockchain. So when the fee crisis comes, it absolutely hamstrings the bitcoin economy, but if you already have funds on the platform or want to send in USD, then a lot of users can trade on the exchange.

In contrast, 2020’s litany of Ethereum transactions and its associated tokens was largely an on-chain phenomenon. Now, centralized exchanges are still very important for price formation, but some DEXs like Uniswap sometimes surpass even the largest centralized exchanges. Since automated market maker DEXes do not require KYC, custodial tokens with third parties, or lengthy startup processes, they are far more convenient for end users. The no-order AMM model is also very easy to use. And certain asset and exposure types like smaller DeFi tokens or liquidity mining can only be done on-chain. Eventually, a vibrant on-chain liquidity industry emerged. Since almost everything traded on these DEXs is Ether or tokens on Ethereum, there is a fee for everything. Unlike centralized exchanges, every trade you make on a DEX must be settled on-chain. Therefore, on-chain fees have always been a consideration.

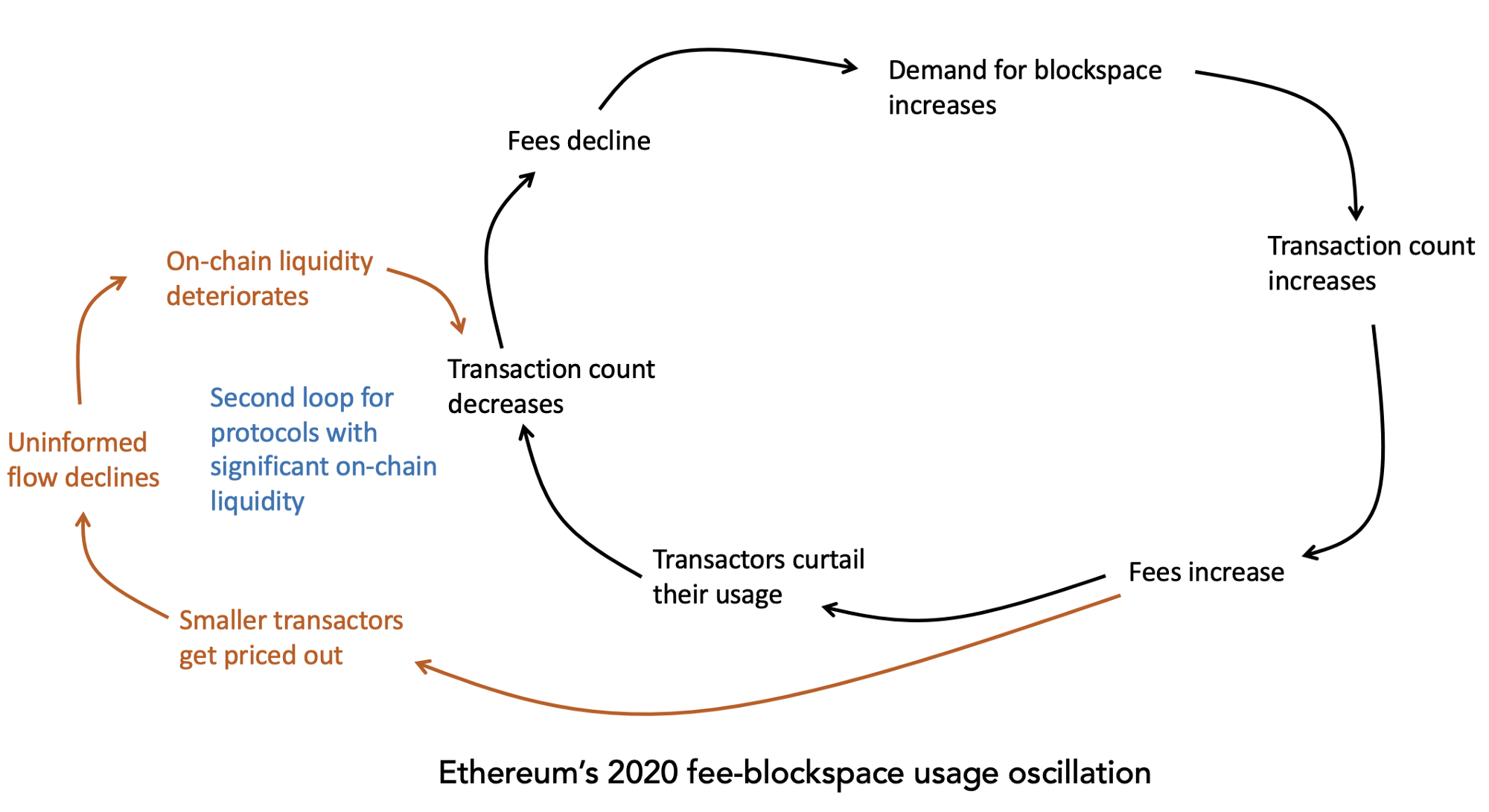

So this is a modified version of the normal fee-tx count volatility model we saw from Bitcoin in 2017, explaining the new dynamics we see from Ethereum in 2020.

So, where does the second loop come from? Why single out heavy chains that need DEX for special treatment?

First, it is important to understand that, as Maya Zehavi said, high fees are a regressive tax on users. Regressive tax rates because fees are not proportional to your assets, but instead are charged in roughly the same way whether you are transferring $100 worth of ETH or $10,000 in fees (fees are a function of transaction computation, not the dollar value of the transaction). This is similar to the way sales taxes are regressive, since groceries make up a larger share of working-class income than the wealthy. So, for wealthy families, the flat 5% sales tax is actually a large portion of the income.

Give an analogy. Imagine a private poker game where the rake is fixed in dollars rather than a percentage of the original value. (Commission is the handling fee charged by the operator to run the game). Players can choose to play a given hand and pay a flat fee, or they can opt out, in which case they pay no fee. There were a variety of players at the table, with a few professionals, some semi-pros and some gamblers who were enthusiastic but not particularly good at poker. Bets can be placed anywhere you like, and to win you not only need to fight your opponents, but you also need to profit from crowdfunding. It's not enough to win, you have to incur transaction costs to win.

If the rake is low, then everyone is actively participating. But when the table operator gets greedy and increases the rake, players with smaller stacks start to feel helpless and have more and more cards in their hands. If they need to raise more than 1/10 of their chips just to play a hand, they will opt out (unless they have an ace). As the absolute value of the rake rises, players are gradually priced out of the game, starting with those with the least bankroll.

When smaller, less skilled players start dropping out of the game, the game becomes significantly less profitable for everyone else. After all, semi-pros rely on unskilled opponents to make money. As every poker player knows, you probably don't want to be sitting at a table with hard-working players and semi-pro opponents on a Tuesday morning. You want to show off your skills on a Friday night, play poker with lazy amateur gamblers, get a quick win, and get drunk.

In an analogy with Ethereum, fees are like bets, and they make prices high for retail investors, who until recently spent a lot of time on Uniswap and other DEXs. But as the handling fee rises to an average of $14 (much higher for a DeFi transaction, such as exchanging ETH for DAI on Uniswap), for individuals with less capital to participate in the transaction or liquidity For mining, it becomes uneconomical. The entire market is controlled by them. And since retail investors are professionals who trade (and profit from) they are an uninformed bunch, so if retail investors don't come out and play, there's not much point in the game. All of this points to falling liquidity and deteriorating trading.

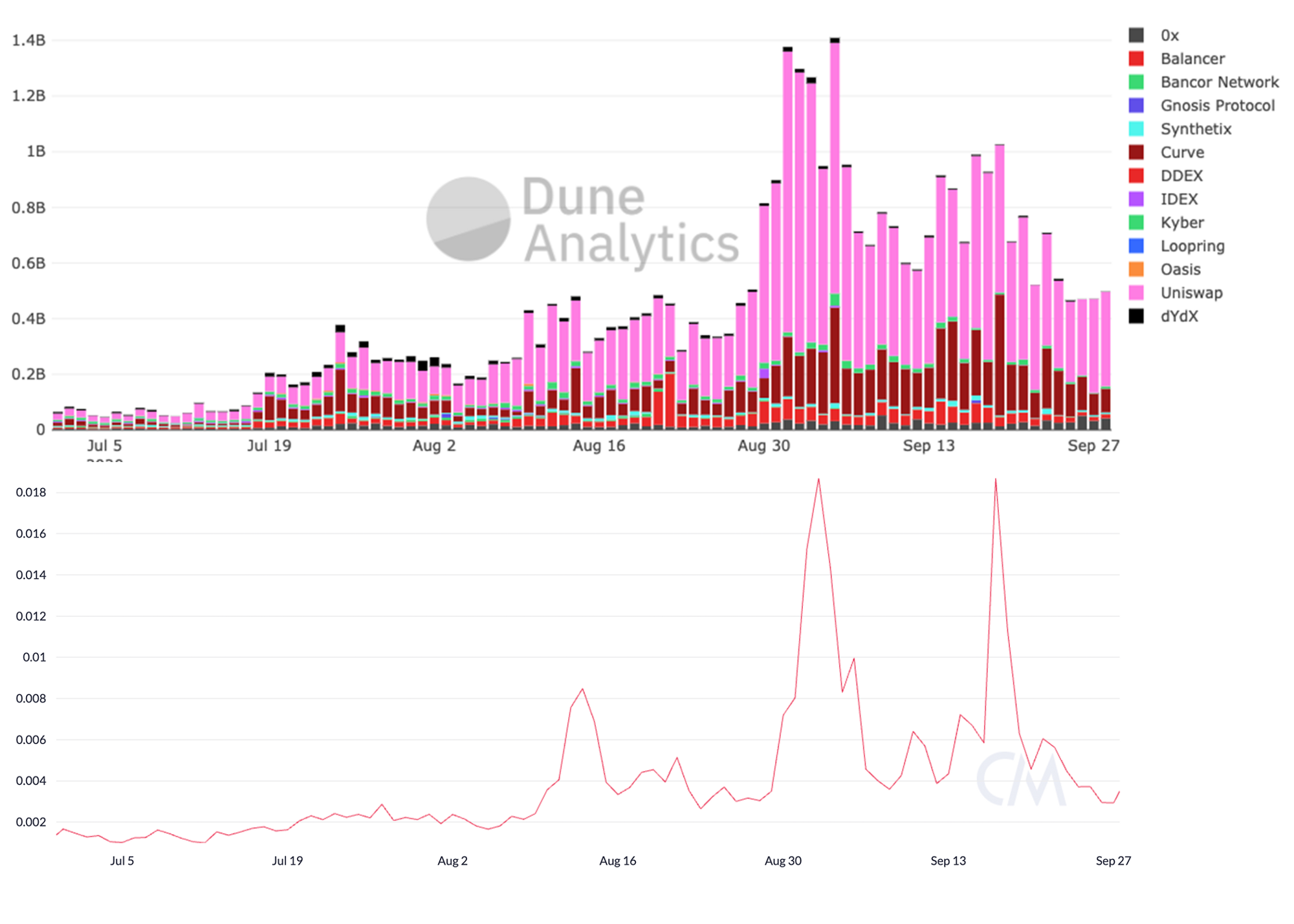

Taken together, this theory is difficult to verify empirically. A detailed analysis of wallets active in DeFi at different thresholds and how they respond to fees, or a comparison of the spread to ETH fees, would be helpful in proving these assumptions. However, there are some indicative figures to refer to. This is the sum of the total amount of DEX provided by Friedrik Haga's Dune Analytics information center, and the comparison with the average transaction fee of Ethereum.

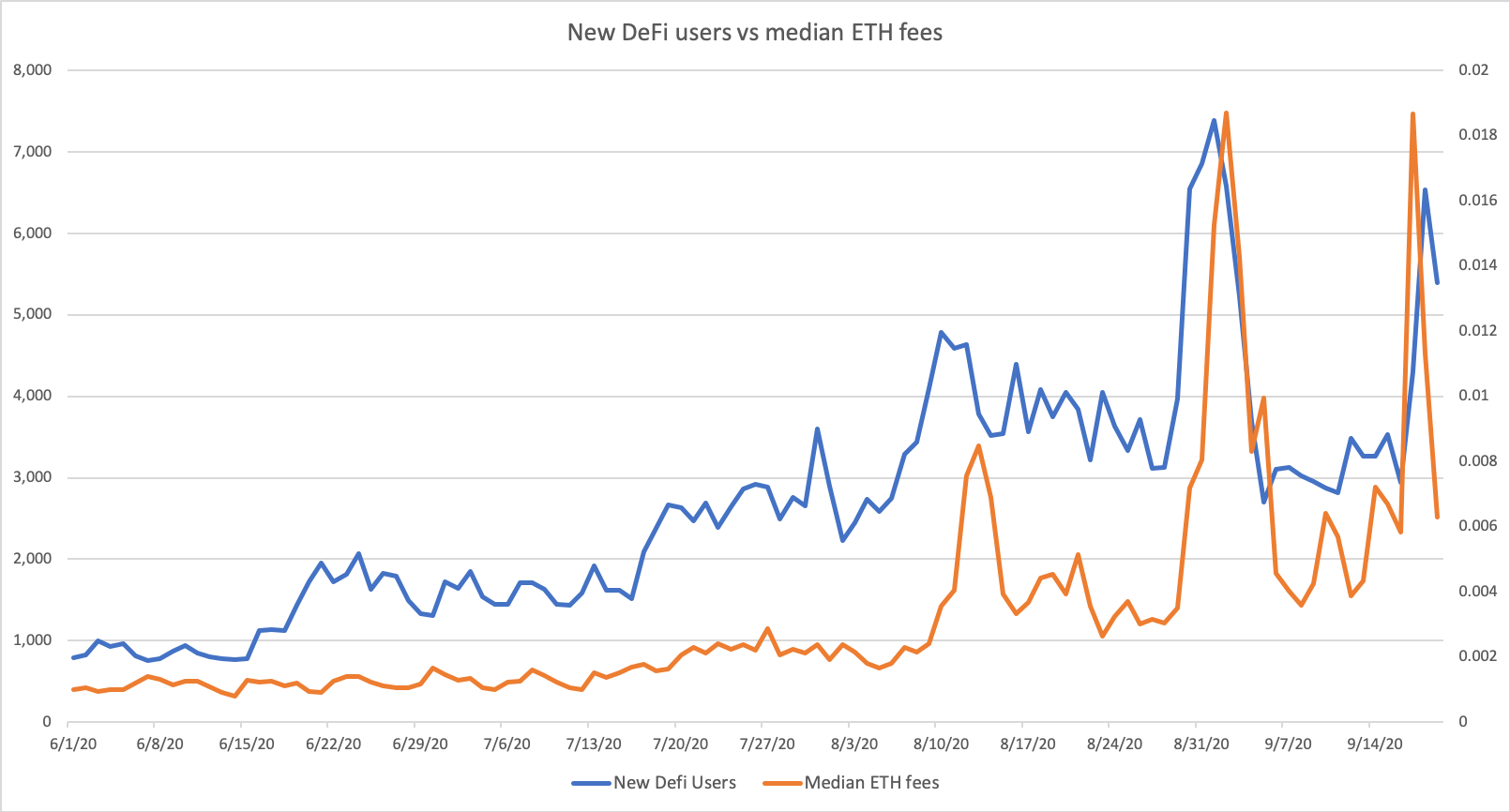

In addition to the two surges in service fees in SushiSwap and UNI token issuance, after the ETH service fee reached a new plateau in mid-August, the daily new participating users of DeFi seem to be decreasing.

The conclusions drawn here are more valuable. It is clear that users with small assets will defer transactions when fees are high, but the direct impact on on-chain liquidity is difficult to measure.

secondary title

Future Prospects for Ethereum Fees

If you consider that DEX volumes and the on-chain liquidity environment generally drive up the price of ETH, then it doesn't take much imagination to make an educated guess about the potential price impact of this phenomenon. With the value of Ethereum serving as the asset-retention requirement for debt-free collateral on top of the DeFi system, the fees that limit usage are likely to drive down the total locked value in the system and add pressure to the price of ETH.

That said, there are some counter-cyclical features that may reduce volatility and insulate Ethereum from fee fluctuations.

secondary title

Unlike Bitcoin, which only officially increased the block size cap once it existed, Ethereum prefers to generate more block space when necessary, although the rate of increase is limited, and elastic block space can theoretically be used to stabilize fees, but this comes at the cost of increased verification requirements, which are already quite high for Ethereum. As Ethereum utilization increases, miners reward traders with higher and higher rewards.

However, the Ethereum community is divided on further fee increases because raising the limit on fees would increase the uncle block rate, make the network more vulnerable to DOS attacks, and make full nodes more expensive to run. In terms of node operating costs, although Ethereum holders are more willing to accept larger compromises than Bitcoin holders, both parties generally agree that simply increasing block space is not the final solution. As a result, there has been little community support to pursue a fully permissive blockspace policy, although the blockspace has some resilience allowing it to handle increased demand.

secondary title

ETH 2.0 / fork

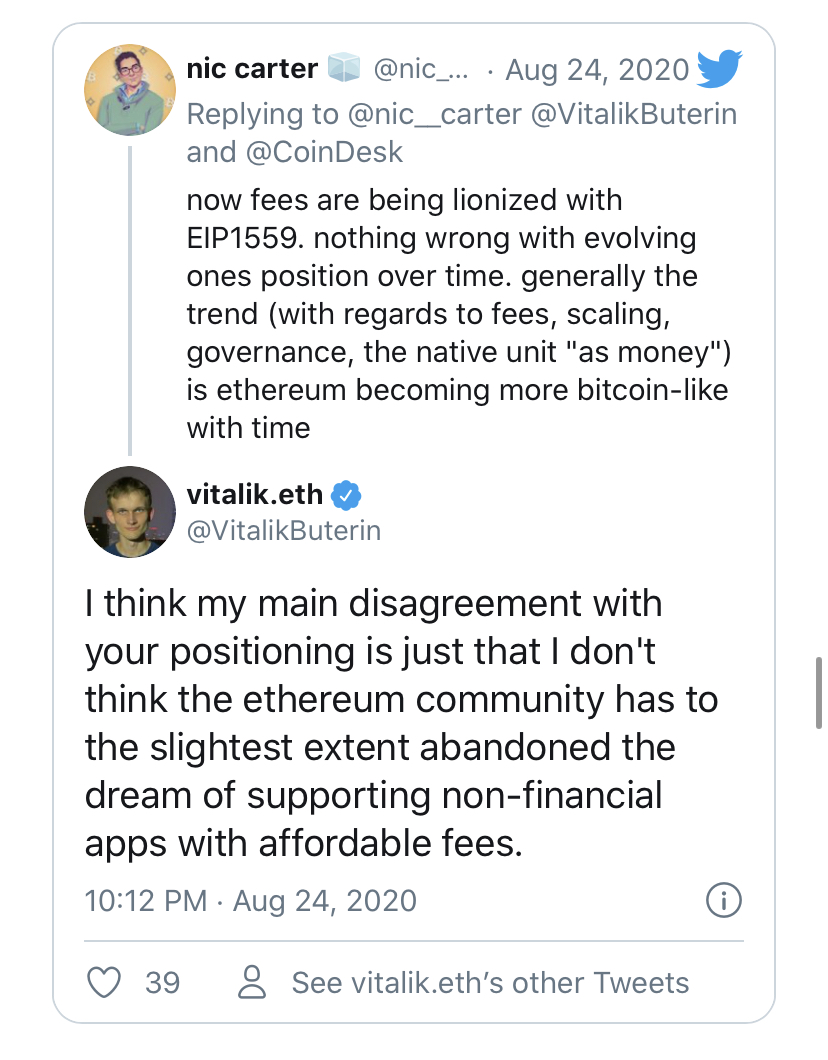

In fact, he pointed out that he still believes that Ethereum has a lot of influence on the future of low-cost blockchains, in which a variety of applications, non-financial and financial, can be used. His proposed solution is Rollups in the near term and ETH 2.0/fork in the long term. Vitalik said that he expects ETH 2.0's capacity to increase by a factor of 100, although he expects that fees may eventually rise to the same level due to demand.

Rollup

I agree more that if your production increases, the world will find more uses for the commodity and the price will go up. Therefore, it would not be surprising to see average fees rise if more block space is created. Regardless, ETH 2.0 still looks far away, making it difficult to predict. But at least, there will be no adjustments in handling fees in the short term.

secondary title

Ethereum currently believes that Rollups are the main way to alleviate the current fee dilemma of Ethereum. There are two main types of Rollups: ZK and Optimistic, but they both generally involve bundling many payments together and greatly increase the economic density of transactions. In theory, while retaining the guarantee of base layer transactions, it also greatly improves TPS. In short, traders rely on intermediaries who broker large volumes of trades and broadcast those trades.ZK Rollup involves broadcasting apparently truncated transaction stubs, along with proofs that the transaction bundle is valid for the ledger. Optimistic involves semi-trusting operators who facilitate transactions, and traders mostly believe that the operators are not malicious. Deterrence is theoretically achieved through a combination of evidence of fraud and financial penalties for misconduct. Currently, ZK Rollups are mostly limited to simple transfers, while certain kinds of Optimistic Rollups (OR) promise to open up the full range of transactions currently possible in Ethereum. For a full analysis of the state of OR, see Daniel Goldman's comprehensive report.

Rollups effectively move transaction data off-chain and put proof of validity on-chain. Bitcoin developers had a similar data-saving vision a few years ago, and pursued Lightning (which could reduce hundreds of thousands of payments to a handful of on-chain transactions), sidechains, and advocated for efficiency-enhancing measures such as batching and the use of SegWit. Thanks to the popularity of Rollups and the apparent rate of progress, Buterin is supportive of them as the best near-term method of scaling Ethereum.

While ETH 2.0 may not be in play yet, Ethereum’s Rollups future is within reach.

There are two reasons why Rollups may not be the panacea for Ethereum’s fee problem. First, it will be challenging to make all block space users owners of the system, especially if they are service providers and can pass fees on to end users rather than insiders. We learned with Bitcoin that if intermediaries can pass fees on to end users, they have no ongoing incentive to invest in more sustainable infrastructure.

Additionally, since Ethereum has repeatedly raised the fee limit to effectively help blockspace consumers (at the expense of validators), a large number of users may spend more time lobbying for resources to increase the fee limit rather than spend a lot of time doing so. Make deals. Similarly, the upcoming large block space of ETH 2.0 may dampen the enthusiasm of large traders for Rollups. Instead, the main contribution of ETH2 at present is likely to reduce the enthusiasm of large traders to make its use more efficient.

Second, the global user base of a blockchain like Ethereum is not exactly developers and advocates, and can actually attract users directly. Ethereum is open to all and does not exclude participation, which is part of the reason for its popularity compared to Ponzi schemes and other niche projects. The coordinators of these schemes (usually some major users of block space) are not necessarily long-term planning or trying to optimize their on-chain traces, but are more focused on making quick money.

On the technical side, Rollups (especially Optimistic) have a different settlement quality than base layer transactions. Vanilla Ethereum transactions are virtually final and carry no chargeback or settlement risk. This property allows for "atomicity", which means that chained transactions either all happen or none of them happen. This enables users to securely interconnect multiple systems without risking a chain failure if a payment in the chain fails to clear. This is a highly desirable attribute, depending on its status as a digital carrier asset. Ethereum has "atomicity", which is composable, allowing smart contracts to safely refer to each other, so that more complex systems can be built without having to evaluate each module.

In addition to deterministic issues, impaired composability is another issue that may prevent an immediate transition to OR. I'm not an expert on Rollups, but I've seen composability issues being the biggest drawback of OR.

in conclusion

secondary title

in conclusion

The difference between centrifugal governors and on-chain fees is that the regulating effect of fees is more of a side effect of a functioning system than a critical design consideration. In public chains, fees exist to ensure non-wasteful consumption of network resources and provide income for validators. Strictly speaking, they are not meant to check system usage. But in reality, they do work, and the braking tends to be a sharp rather than gradual.